Those following Turkey’s local elections will be hearing the name Erbakan pretty often in the coming week.

Necmettin Erbakan was the standard bearer of Turkey’s Islamist movement in the 70s, 80s and 90s. A group of his younger lieutenants eventually splintered off and founded the AK Party. Erbakan never really forgave them, accusing them of selling out the Islamist cause.

Erbakan’s youngest son, Fatih Erbakan, is now in politics and has revived his father’s “Refah” (Welfare) party, calling it “Yeniden Refah” or “Refah Anew.”

I thought it might be a good occasion to take a look at back at Erbakan, his place in Turkish politics, and how his message reverberates between the AK Party and Yeniden Refah today.

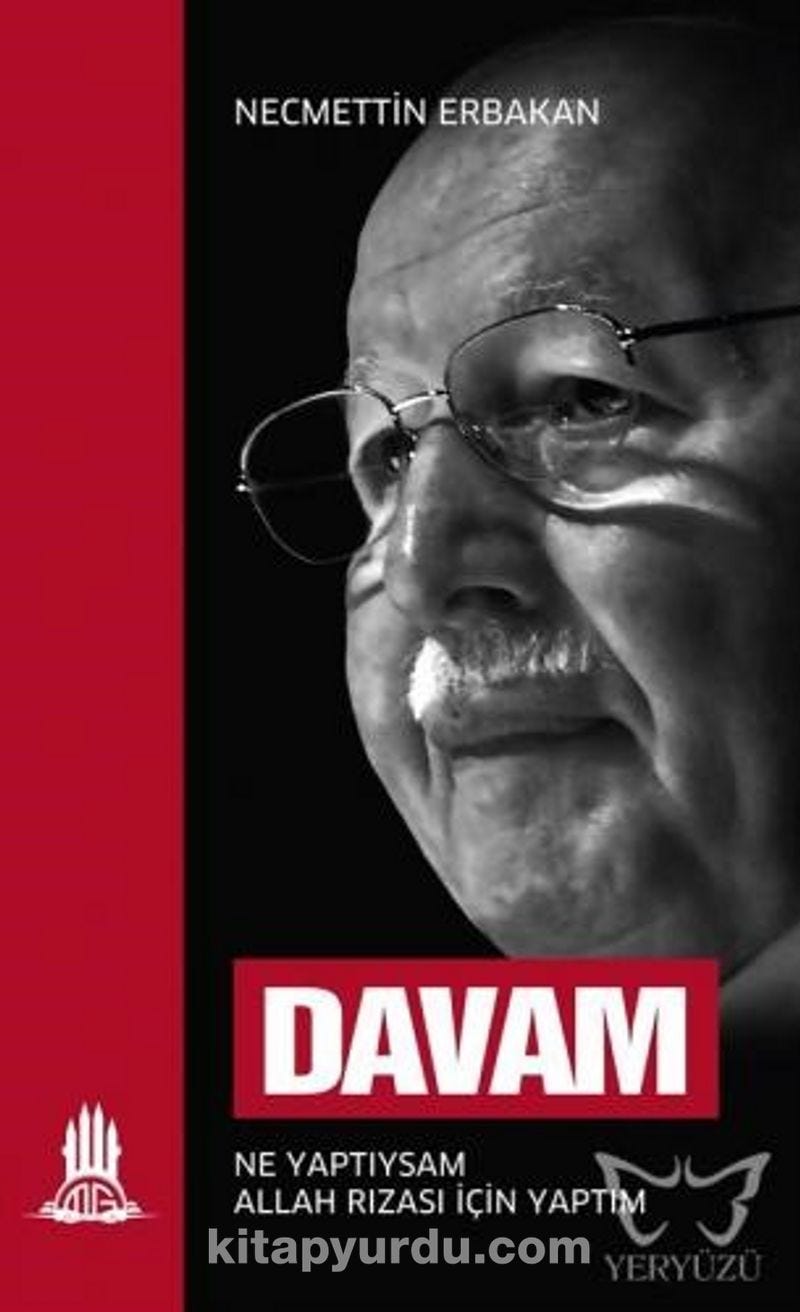

It’s not easy to categorize this book. It’s somewhere between an autobiography and a manifesto, meaning that it roughly narrates Erbakan’s life, but also has long stretches of theory. Erbakan died in 2011 and the book was published two years afterwards by Milli Gazete, the newspaper and publishing house of Milli Görüş (National View), Turkey’s main Islamist political movement.

Erbakan died at the age of 84, and was pretty far gone towards the end of his life. The book sounds like he spoke into a tape recorder and people who were familiar with him recorded it, edited the transcript and made it into a book. The stories feel well-worn, the kind that someone like Erbakan would have been telling his entire life.

The title of the book is “Davam,” which translates to “my cause.” That immediately made me think of another right-wing autobiography-cum-manifesto that sells pretty well in Turkey. The subtitle is “ne yaptıysam Allah rızası için yaptım,” (“whatever I’ve done I’ve done for the sake of God.”) I think that’s perfect. Erbakan believed that he was nothing short of a genius, and packaged his indomitable ambition into these kinds of pieties. It’s ultimately why he wasn’t able to stomach the success of the AK Party, and why we’re seeing the Erdoğan-Erbakan split persist in our present day.

But without further ado, let’s jump into the text.

Introduction

Erbakan was born in the Black Sea town of Sinop on October 26, 1926, just three days shy of the third anniversary of the Republic. His father was a judge, and he attended Istanbul Erkek Lisesi, an elite boarding school that educates students in Turkish and German. Erbakan writes that he was head of his class there, then went on to Istanbul Technical University (ITÜ), one of Turkey’s two top engineering schools. In 1951, he went to Aachen Technical University in Germany to study mechanical engineering.

In Aachen, Erbakan writes that that he worked with a “Prof. Schmidt” to make engines used in military vehicles. He earned his PhD studying diesel engines. It seems that this is where Erbakan developed what came to be known as very rigid ideas about defense technology. He recounts how Prof. Schmidt told him about how they (the Germans) lost WWII because their tanks had cumbersome engines that kept breaking down in the deserts of North Africa and in the Russian winter.

It occurred to me at this point that Erbakan spent much of his 20s with scientists who had been deeply involved in the Nazi war effort just a few years before. Erbakan never mentions the word “Nazi” nor does he comment on the cohort’s political beliefs. There is, however, an air of respect in the way he talks about these scientists and the way they think about the world. He is impressed, for example, that even in its defeated state, Germany wanted to build engines at home rather than import them. That’s what great nations did. They made sure that they weren’t dependent on outside powers.

For the remainder of the long introduction, Erbakan jumps straight to his ideas about industrialization in Turkey. Once back home, he was convinced that Turkey could industrialize from zero to hero, just like Germany. The only reason that didn't happen was that the Kemalist elite in Turkey was enthralled to their connections to the United States. He calls this the “montajcı zihniyet” or the “assembly mindset,” meaning that they bought machine parts from the U.S. and had them assembled in Turkey.

This is also a common complaint today’s Islamists levy against the early Republican elite. They argue that Turkey could have developed its own defense industry from the start and been less reliant on NATO, but that the Kemalist elite was lazy and stupid at best (treasonous at worst), and scrapped early attempts at indigenous production. The state broadcaster TRT has aired a short docudrama about the lives of Turkey’s defense industrialists entitled “The Heroes of Turkey's Defense Sector.” Erbakan’s story makes up the first episode:

Most of it is based on the introduction in Erbakan’s book, often verbatim. This is grossly negligent to say the least, since Erbakan doesn’t cite any sources, so his narrative isn’t really fit for reputable journalists to dramatize in this way. Common TRT fare these days.

I'm not a specialist on the political economy of the early republic and can’t make an authoritative criticism of these kinds of claims. Turkey did have indigenous programs and did scrap them once very cheap American military supplies came into the country. So it's very clear that the country made a decision not to develop an indigenous arms industry in the 1950s. The question is whether that decision was based on a disbelief in Turkey's own industrial abilities, or a more common guns vs. butter calculus. I would think it's the latter.

Erbakan's account gets very cartoonish very quickly. He recounts how, for example, he held a presentation to senior military commanders, and when he was done with his slides and turned the lights back on in the room, he saw how all the military brass was in tears because they were touched by his patriotism. I just don’t see that happening. In another instance, Erbakan secures investments for an engine factory, has it built and produces at a decent clip, but the government entangles him in so much red tape that he has to shut it down. That one is more believable, but still simplistic.

In 1969, Erbakan became president of the Union of Chambers and Commodity Exchanges of Turkey (TOBB). He says he was trying to revolutionize Turkish industry, but couldn’t get his ideas accepted among “domestic and foreign capital, as well as the government [iktidar].” That’s when he decided to go into politics.

Politicians always have this sort of origin story, but the truth is that someone with Erbakan’s ego would have gone into politics anyways. There’s passages like this all over the place:

Sometimes they ask us: “You graduated at the top of all schools. You have the brain of genius. You have made great discoveries in the world of science. Wouldn’t it have been better if you had remained a scientist, made scientific discoveries and served humanity in this way?”

Our answer is as follows: “You can be a professor at a university, you can win Nobel prizes, but what good are your Nobel prizes if the people of your country are hungry, in misery and hardship, if 300 thousand children in the world are dying of hunger in poverty, as they are today?”

It’s precious to make such humanitarian claims, after several pages on heavy industry and military technology. Erbakan’s politics, like other right-wing figures, was to pursue national glory through military and industrial power.

Creation and Man

This chapter is thematic, rather than autobiographical. Here Erbakan reflects on creation and the concept of jihad.

The section on Islamic creationism is fun if you’re interested in this sort of thing. I’m still topped out since childhood, so couldn’t really enjoy it very much. Contra Darwin, humanity didn’t evolve, but was designed by a micromanaging God, etc. It’s worse if, like Erbakan, the person delivering the sermon is an engineer. He makes a point of showcasing some basic biology and physics to give the whole thing a veneer of scientific validity. Like this:

One of the most important proofs of the existence of this divine order is the unknown property of water. All solid, liquid and gaseous objects in the world expand and decrease in density when heated. Every object that cools contracts and its density increases. There is only one exception to this, and that is water. Only water does not obey this rule. From 100 degrees to +4 degrees, water shrinks in volume as it cools. The heaviest water is water at +4 degrees. Therefore, there is no water colder than +4 degrees at the bottom of rivers, lakes and seas. If water at +4 degrees continues to cool down and its temperature continues to decrease until +3 degrees, +2 degrees and +1 degree, its volume starts to expand. Thus, as the weight of the unit volume decreases, it rises to the upper layers. When it reaches zero degrees, it reaches the largest volume and rises to the top of the water layer. Thus, the freezing of rivers, lakes and seas starts from the top, not from the bottom. This seemingly ordinary and unremarkable rule, as a divine mercy, makes it possible for aquatic creatures to live and reproduce.

I think Christian theologians do this less because they don’t have to contend with accusations of civilizational backwardness quite as much as Islamists do. Islamists also tend to be quantitative minds, while Christian fundamentalists are more qualitative in nature.

Anyways, from the natural world, Erbakan moves on to the world of man. Having created humanity and imbued it with free will, God has made life on earth into a contest between good and evil, [hak ile batıl]. To be human is to be confronted with this decision, and God’s revelation (Islam) is here to guide humanity towards good and away from evil. Simple.

Here Erbakan wants to make something very, very clear. Islam isn’t just about praying five times a day and giving money to the poor and reading the Quran. It’s about jihad, the all-out struggle for justice on earth.

This was important for Islamists of Erbakan’s generation. Turkey’s Kemalist regime was implying that the “real” Islam had to be quietist, that it was a (somewhat ascetic) discipline that could be practiced in the privacy of one’s home, that it didn’t really have a communal or political dimension. Kemalist secularism was therefore not against Islam per se, it was simply confining it in its clearly delineated space. Like all Islamists, Erbakan objected to the idea that Islam could be confined. Properly understood, Islam had to suffuse all aspects of life, including politics.

There’s a hadith here that Erbakan cites, and it sounds like the kind of thing he has told a million times throughout his life (I have an ear for these things). I’m going to quote it in its entirety, but you can skip it if you want. Here it goes:

We do not conduct politics, we conduct jihad. The person who does not make jihad cannot pass the test of the world.

Who says this? It is stated in a hadith: a bedouin came to the Prophet (s.a.w.). He said, “O Rasulullah [the prophet of God], I want to become a Muslim, what should I do?” The Prophet (s.a.w.) said two things: “One, you will bring the Shahada [the profession of faith]; two, you will pledge your allegiance to me.”

The bedouin said, “How will I bring Shahada?” The Prophet (s.a.w.) described it. The bedouin brought the Shahada and became a Muslim. “Now you will pledge your allegiance to me,” the Prophet said. “What will I pledge my allegiance on, O Rasulullah?” asked the bedouin. “The Shahada, prayer, fasting, zakat, pilgrimage and jihad.” Our Master listed six things.

When the Bedouin heard this, he said: “O Messenger of Allah, I come from a large tribe. We have three camels. Their milk is only enough for us. Let us not give zakat. You are new to me. But I know myself better than anyone else since I was little. I am a very cowardly man. Allow me not to pledge my allegiance for jihad. Because if I promise you that I will work with all my might to establish truth and justice on earth, and tomorrow, when I encounter a difficulty in this endeavor, I will turn back because of my cowardice, then my punishment for having made a promise and turned back will be more severe. So it is better not to make any promises in the first place. Let me not make promises on jihad and zakat. But I will fulfill all the other conditions you mentioned, including the Shahada, prayer, fasting and pilgrimage, as required, and even more."

Our Master (s.a.w.) warned the Bedouin: “But with what will you go to Paradise?” He has faith, he has brought the word of God [Shahada]. You can go, but only eventually. He is praying. Yes, he will pass the test of prayer. He fasts. He will pass the test for fasting. Whether you go to perform the Hajj or not, you will attest for it. But how will you account for the obligation of jihad? That is why the one who does not fulfill the obligation of jihad will not be able to pass the worldly test.

It’s exactly opposite to the argument many liberals would have, that one’s political beliefs and faith can be friendly neighbors without infringing on each other’s business. Erbakan hued closer to the liberal argument when speaking to soldiers, and spoke more freely to his own followers, as he is in this book.

Erdoğan of course, took that two-pronged approach (let’s be nice) to new heights, and Erbakan bitterly resented him for it. He takes a quick stab at the AK Party here too:

You will say 40 times in prayer, “O Lord, don't lead me astray to the path of the Jews and Christians!” and then after bowing, you will say, “I will bring Turkey into the European Union.” You will become a strategic partner with the U.S.A. and Israel. For 11 centuries, you will leave a civilization that represented truth and justice on earth and run after the West. What do you promise to God in prayer, what do you do after you bow?

Are you aware of what you are saying, O Muslim!

Remember that Erbakan only saw the first decade of the AK Party, when it was still a fairly liberalizing force.

Our Cause of Islam [İslam Davamız]

This is another thematic chapter, and a rather long one. here Erbakan covers the origins of scientific knowledge and Cold War ideologies.

His main argument is that Islam isn’t “backwards” as his opponents suggest, but scientific and progressive. He’s upset that people think of the West as the home of science. That, he says, isn’t just a misconception, it’s a great lie based on intellectual property theft on a civilizational scale:

The founders of what we today call Western science, of physics, chemistry, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, history, geography, are all Muslim. This of course is a great claim, but we are here to prove it.

What follows is a rant of at least 30 pages in which he goes through each discipline, cites its accomplishments and argues how the Muslims got there first (the Americas, the concepts of sine/cosine, pi, etc.) and how Westerners stole their discoveries. Some parts of it are based on historical fact, others less so.

It’s obviously a very thin argument, but Erbakan’s intention here is to invert the spirit of defeat in the Muslim world. He wants to initiate a virtuous cycle by inspiring self-confidence in his Muslim audience and get them involved in the sciences. Erdoğan of course, has advanced this line of argument beyond Erbakan’s wildest dreams. He often credits his accomplishments, including the likes of the Bayraktar drone, to a confidence born of this kind of argument.

The next section in this chapter is on the two superpowers during the Cold War. Erbakan is writing this book in the 2000s, but like many people who lived through the Cold War, you can tell that he still mentally inhabits that world.

He recalls several visits he made to the Soviet Union, and says that it was a deeply unnatural system. Without the profit incentive, he says, peasants didn’t produce food and factory workers didn’t want to work. He doesn’t really cite any work on this, but is happy to confide himself with common sense analysis. The Communist system is so blatant inadequate, Erbakan says, that it would be naive to think that it’s based on a well-intentioned economic theory. It is, after all, based on the work of Karl Marx, a German Jew. He suggests that it would make more sense to think of the Soviet Union as a sort of large experiment of the global powers that rule the world (more on antisemitism in part II).

Erbakan seems particularly horrified by the idea of women working hard jobs under Communism. He apparently visited a factory in East Germany where he witnessed women working with hot steel on a factory floor, and he cites it in two different places as an example of how disfiguring the system is to family structures.

The Capitalist system of the West, he says, is better because it runs on competition, which means there’s more production. The problem is that it’s too comfortable with inequality. The rich are too happy to just shrug their shoulders and say that poor people should work. Women can have more feminine jobs (like being secretaries) but can’t be happy unless they work just as much as men, which means that they are bound to feel either inadequate or burned out.

The solution, of course, is Islam. Trade is embedded into Islam, so it maintains competition without the interest-based financialization of the Western system. The Islamic system is spiritual at heart, so it maintains the organic fabric of society while yielding high output. There’s a section on women here that could be considered fairly progressive among Islamist circles: they can work and participate in public life according to their nature, but ultimately find happiness in building big families.

When I think of the woman of the Eastern Block in my memory, I think of a type of woman in heavy labor, sweating while working an [industrial] rolling machine. When I think of the woman in the West, I think of an unhappy woman working as much as men for the sake of equality, and being treated in ways that are not suited to her nature. When I think of the woman in Islam, I think of a creature who holds even heaven under her feet.

That last bit is a reference to a bit of frequently-cited scripture (al-Nasā'ī 3104) saying that paradise is to be found under the feet of mothers. It’s very common for Islamists to respond to accusations of misogyny by saying that they don’t hate or demean women, that it’s just the other way around - that Islam exalts women (i.e. mothers) as holy creatures. Make of that what you will.

That’s the first part of the book. Part II will be in your inbox in a couple of days.

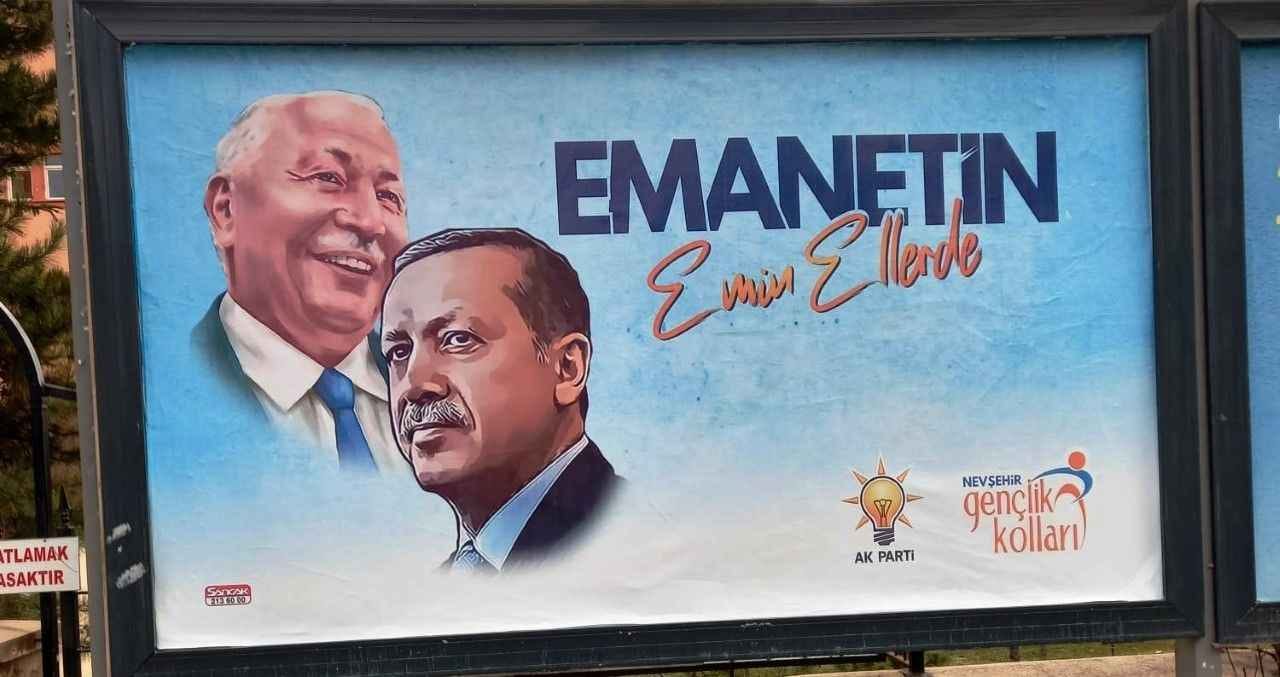

I’ll leave you now with this election poster from 2022. It roughly reads “your legacy is in safe hands,” with an aged, faint Erbakan in the background and a strong lines depicting Erdoğan in the foreground.

Erbakan never embraced the AK Party. His two successor parties, Saadet and Yeniden Refah, still don’t for the most part. The AK Party, however, still claims Erbakan’s mantle, and carries the vast majority of his former supporters.

"There is only one exception to this, and that is water. Only water does not obey this rule."

There are still some Christians who attempt these "checkmate, atheists" arguments, but I feel there are fewer around now than when I was a kid. Lucky noone told Erbakan that plutonium is also a miracle substance blessed by God with a negative coefficient of thermal expansion, or his chapters on defense might have been even scarier.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Materials_that_expand_upon_freezing

https://i.kym-cdn.com/photos/images/original/000/282/360/62b.jpg