I’ve been getting a lot of questions about violence before or after the elections.

Let me say at the outset that political violence is more common today than most of us think. The U.S. and Brazil saw their parliaments stormed after their right-wing leaders lost elections. India regularly sees violence against Muslims, and there were pretty destructive riots on the streets of Paris recently. We think of Japan as a pretty tranquil place, but their Prime Minister was assassinated just last year, and the current one was pipe-bombed a couple of weeks ago. That’s just off the top of my head.

Turkey has low-to-medium levels of political violence more or less running in the background at all times. Now consider the significance of the upcoming elections: we aren’t just voting on governments, we’re voting on two different regimes, with almost mutually exclusive sets of elites. The stakes are stupendously high. It’s not a question of whether there will be more violence - there already is a bit of a spike - it’s a question of how much and to what end.

I’ll cite two recent publications I found useful in thinking about the issue.

Spontaneous violence

The first source I want to discuss is a column by Ali Duran Topuz, a highly respected, left-wing critic. Topuz writes about what I’ll call “spontaneous violence,” meaning unpredictable, seemingly random acts of political violence, either by individuals or mobs.

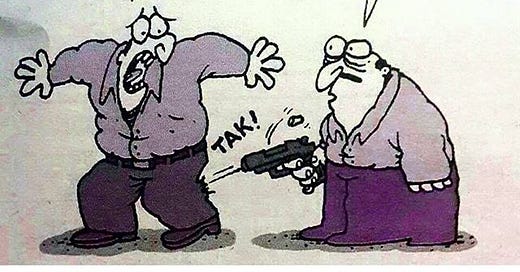

There’s no shortage of examples in recent years. There was a serious attack planned (and thwarted) on Kılıçdaroğlu during his 2017 “march for justice” and a man punched him at a funeral in 2019. IYI Party members and sympathizers have been beaten up on the streets, one MP was beaten up in parliament and had to be hospitalized. In recent weeks, unknown assailants in Ankara fired shots at İYİ and CHP headquarters. Once Kılıçdaroğlu released a video openly saying that he was Alevi (an unorthodox sect in Islam) a man at a funeral shouted at him and had to be pulled back. The following day, a group of AK Party supporters in Adıyaman attacked a CHP convoy.

Topuz points out that the perpetrators of such attacks don’t suffer serious punishment. If anything, Erdoğan and those around him verbally pile on. After an aggressive mob surrounded Akşener in Rize in 2021, Erdoğan said the following:

The bride is being taught a very good lesson in Rize... Pray again that they taught the bride a lesson without going too far. This shows the decency and manners of Rize’s people... This is just the beginning. There will be many more to come. You just wait. These are still [your] good days.

It’s very clear that Erdoğan is on the side of the angry mob here. (Yes, he calls Akşener “the bride” because her husband, like him, is from the Black Sea. It’s his twisted way of connecting to her but subordinating her at the same time.)

Topuz argues that it makes no sense to look for some kind of smoking gun in instances of spontaneous violence. It’s a bit like Donald Trump on January 6 - did he plan it, or did the mob act on its own? It really doesn’t matter. These kinds of leaders provide the environment for random acts of political violence.

The following objection can be raised: the government cannot be organizing these, they are the results of tensions around elections. That's what [Minister of Interior] Soylu says. The answer is not difficult: Of course, an “organization” does not need to be proven. Because the government does not become responsible only when it is the “regulator;” by calling for violence, praising it when it appears (as in the case of Akşener) and not punishing it when it happens, you have already paved the way. The “street” always follows the state, it follows power. It is not for nothing that the names of the attackers are people in contact with the ruling parties.

That symbiotic relationship far-right leaders say they have with “their people?” It’s real. During the 2013 Gezi protests, Erdoğan infamously said that “right now, there is at least 50 percent of this country we are barely keeping in their homes,” meaning that if he let them, his supporters would go and violently suppress the protests on their own.

People remembered that statement. On the morning of July 16, I was in front of parliament. The coup had failed. The men who had gone out to face the tanks were still there. These weren’t teachers and accountants, they were rough men who had just survived a violent confrontation with a putschist military. They were celebrating with chants, slogans, and hand signs. I overheard a conversation between two of them in front of me. They were talking about Erdogan’s comments at Gezi: “didn’t Tayyip say it? He said he’d call us out on the streets, and he did!”

Organized violence

Interviews with Ahmet Şık are always worth watching in full. There’s a lot to unpack here, but I’ll focus on a point he makes towards the end, because it helps us think of the ways political violence might occur.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Kültürkampf to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.