This is the third part in my series reviewing the semi-autobiography of Necmettin Erbakan, the founder of Millî Görüş (National View), Turkey’s main Islamist movement.

Part I was mostly on Erbakan’s early years as an engineer and the basics of his Islamism. Part II was on a long chapter called “the powers that rule the world” in which he gave a sweeping overview of modern history as he sees it.

I thought I’d make it a three-part series, but couldn’t quite fit everything into a single post, so there’s going to be a final post tomorrow or Friday.

Our Cause of Islamic Unity (İslam Birliği Davamız)

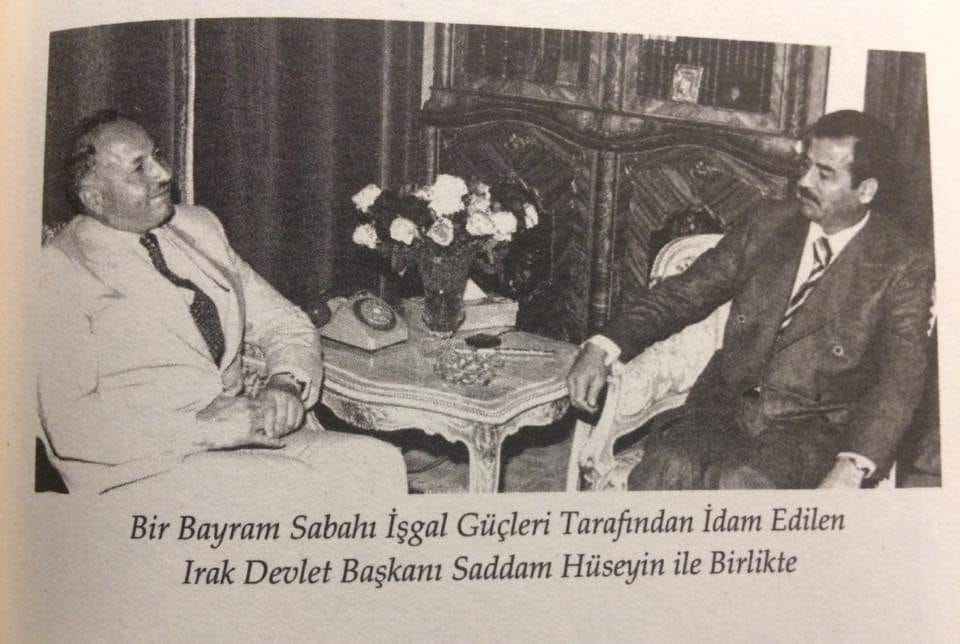

I started reading this section expecting abstract notions of Islamic unity, but there isn’t much of that there. Most of it is a narrative of Erbakan jet-setting between Islamic countries in the lead-up to the first Gulf War. It starts in the summer of 1990, when he visits Baghdad to talk to Saddam Hussein, but then jumps forward to December 1990 - January 1991. By this time, Saddam has invaded parts of Kuwait and the Americans have been building up forces and are preparing to attack Iraq. Erbakan is not in government at this time, but is trying to convince leaders in the Islamic world to resolve the Gulf Crisis and deny the West an excuse to intervene in the region.

It’s clear that Erbakan got lots of time with Saddam during these months, and he quotes him at length, often across several pages. These quotes, like all others in the book, are not to be read verbatim. Erbakan just recreates figures from his memory, often making them out to be saints or devils. His Saddam is a good, honest Muslim who is trying to resolve an understandable territorial dispute with his southern neighbor. Saddam’s overriding concern is to resist Western interventions into the Islamic world, which Erbakan, of course, shares.

There’s a flashback here to Erbakan’s days in Germany, when he was first confronted by Western designs on the Middle East. He says that in the spring of 1952, he was invited to a secret conference of the German aviation research agency (Deutsche Luftfahrforschung, best known for having developed the V1 and V2 rockets) held at the Kürhaus Hotel in Aachen. I did some basic googling, and the details of the institution and the hotel check out, but haven’t been able to verify anything beyond that. Erbakan reports that the conference reflected on ways to steal Middle Easter oil. There’s long quotes again, like this one by ESSO (now ExxonMobil) general manager “Dr. Müller,” who’s opening the session to this secret conference:

“I have invited you to a conference entitled ‘Today's Arabia,’ but the name of the conference is due to its secrecy. The main purpose of the meeting is this: I come from Dammam, the new oil region of Saudi Arabia. Together with the Americans, we have found the world's richest oil resources. In these secret meetings that we have planned to be held with select people from important cities in America and Europe, we want to consult on how we can ensure that this enormous wealth is used for the benefit of the people of the Western world. Therefore, after giving you brief information about this great wealth, I will be asking for your recommendations.”

Sounds a bit like a Bond villain, but Erbakan firmly believed these stories, and so did his followers. He says that some awful things were said about Islam and the local population, but that he couldn’t speak up because he was there on behalf of his mentor, Prof. Schmidt. Erbakan then went back to his room and wrote out a 40-page letter home about the awful things he heard at this secret conference.

I don’t know what to make of the anecdote. It’s conceivable that young Erbakan found himself at a conference where Gulf oil was being discussed. It’s no secret that U.S. foreign policy was heavily invested in controlling the flow of oil, and that they made long-term commitments to the Gulf kingdoms to this end. It’s plausible that some German scientists were talking about this in the 1950s. Erbakan’s narrative isn’t aimed to mount an argument about this, it’s to project himself as a character who has been to the belly of the beast and back. It boosts his mystique as the worldly scientist who is unveiling the secrets of the global conspiracy. Turkey’s far right-discourse is replete with such stories. Go ask Ümit Özdağ about how the Americans offered him the leadership of the “Great Middle East Project” in a secret meeting, and how he gallantly refused.

The narrative shifts back to the Gulf Crisis. Erbakan is traveling to countries like Libya, but always flying back to Turkey in between to take part in the election campaign that was gradually getting started. (The election was on October 20, 1991, and Erbakan got 7.2%). It’s very clear that he’s trying to fulfill the role that Erdoğan today still aspires to, which is to create a pan-Islamic, or what might today be called “South-South” forum to talk through problems and thereby avert Western intervention. This failed, Erbakan thinks, because the Islamic world didn’t have Turkish leadership:

The Islamic Conference, which convened while these events were taking place, could not find a solution to the Gulf Crisis. It was divided into two and was in a position where it could not discuss issues with the participation of all its members. The government in Turkey, which should have played an arbitration and mediation role between brother Muslim countries, took sides under the command of U.S. President Bush from the very beginning of the events and lost the opportunity and qualification to act as an arbitrator between brother Muslim countries.

In the absence of unity, Muslim countries couldn’t put together an international armed force. Without such a force, it was left up to the Americans to amass forces in the Gulf and eventually invade Iraq:

If a peace force formed with the participation of Muslim countries could undertake the defense of Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, this force could, in time, form the first core of the Muslim Countries Defense Cooperation Organization.

Erbakan calls the American-led military force “Ezen Güç” meaning “the Oppressing Power.” It’s a special term, like the Secret World State (Gizli Dünya Devleti, GDD). From a linguistic point of view, I think part of his problem was that he kept inventing new words and concepts for the same thing: the Jewish conspiracy running the modern world.

The section ends with more Saddam quotes, diatribes about how he wanted Islamic unity, how things could be resolved between neighbors and fellow Muslims, etc. The word “peace” comes up a lot.

Our Cyprus Cause (Kıbrıs Davamız)

The Cyprus issue is often seen as the province of the old Kemalist elite, and especially the military. That’s probably because defense was traditionally their purview, and Turkey’s Aegean region, as well as the Turkish inhabitants of the Island, are on the whole fairly secular.

Erbakan pushes against that a bit. He opens with a narrative going back to the 7th century, when the first generation of Caliphs began to raid some cities in Cyprus. He makes it sound a bit like the Island became Muslim during this time, which it did not. It was under Levantine control until the Ottomans took it in the 16th century, during which time it acquired a multi-confessional makeup, including Muslims.

Today, he says, Cyprus has strategic importance in the Islamic fight against global Zionism. It must be denied to the enemy, he says, because it can act as a base for attacks on the entire Middle East:

If, God willing, this island were to be in the hands of foreigners, it would be very easy to jump from here to Anatolia and quickly reach every part of Anatolia from the air bases here. In fact, it is possible to destroy various parts of Anatolia with the medium-range missile launchers here. Cyprus looks like a large aircraft carrier floating in the middle of the Mediterranean.

Nothing is more Erbakan than imagining Cyprus as a launching pad for rockets aimed at the Anatolian mainland. But let’s get back to it:

Whoever captures it [Cyprus] will dominate the Mediterranean. That's why it has vital importance for Turkey. If even the slightest concession was attempted in Cyprus, the rest will come like a rip in the sock. First, it would cause the loss of Cyprus. Then [we would lose] the Aegean, then Eastern Anatolia, then Armenia would come, and Pontus, and Byzantium. . .

So Cyprus is the first among a series of dominoes. The Turkish presence there must be maintained at all costs, otherwise Turkey will be encircled, etc.

Erbakan then goes into his account of the 1974 Turkish intervention in Cyprus. This is important because he was actually “in the room” for once. Bülent Ecevit was chairman of the CHP and Prime Minister, while Erbakan, as chairman of the National Salvation Party (MSP) was his coalition partner and officially his deputy. Ecevit usually gets all the credit for Cyprus, which I think is right. The buck stopped with him, after all. He made the diplomatic talks. He gave the order to intervene on the island. He decided when to stop and how to position Turkey. That’s why he was hailed the “conqueror of Cyprus” in the aftermath (a title, by the way, he disliked.)

Still, Erbakan, as is typical to him, is trying to take all the credit here. He argues that he conducted critical meetings with the military when Ecevit was holding talks in London ahead of the intervention. He also says that he was in tune with the generals, who wanted to take greater parts of the island, but that the Ecevit administration was timid in the face of Western pressure.

This was primarily a matter of timing. At some point it was clear that Turkey had to declare a seize fire, but the more the seize fire would be pushed back, the more time the military would have to occupy new parts of the island. Very basic. Erbakan says that he was trying to buy the military time, but that Ecevit jumped the gun:

We, as the MSP wing, said that we could agree to a ceasefire on the condition that it was “declared at 5 o'clock the next day.” However, Mr. Ecevit, probably due to a habit coming from journalism, did not wait until 5 o’clock that day and announced the ceasefire at 11:00. According to later findings, unfortunately, we lost part of Nicosia due to the early declaration of the ceasefire.

As Milli Görüş [National View, the Islamist movement], our goal in the Cyprus Peace Operation was to take all of Cyprus under our control. There were several important reasons for this: One of them was that we were carrying out this operation as the guarantor state. Our guarantorship is over the whole of Cyprus. Therefore, it was our duty to ensure the safety of life throughout Cyprus. Secondly, we have many brothers on the Greek side [of the island]. There are also massacres in the villages there. If we take part of the island under our control and leave the other part out of our control, the massacres there will continue to increase. Most importantly, our bargaining margin would be higher when we sat at the table. Because there was no difference between taking all of Cyprus and taking half of it. The outside world was not merciful to Turkey at any point.

So Erbakan’s main complaint is that Turkey didn’t push to get Cyrpus as a whole.

There are also two minor issues that he is bitter about. First, he thinks that Larnaka, a city on the South-Eastern coast of the island, could have been taken with a little more time. Second, he laments that the city of Maraş (Varosha in Greek), was left in the DMZ, and was thus to remain uninhabitable.

It may sound like Erbakan is being his crackpot self, but the ideas he is advocating for are alive and well today. Erdoğan himself channels them regularly. He said at the operation’s 49th anniversary last year that Turkey would be in a much better position if it had taken the whole of the Island. He lamented the loss of Larnaka, and is now taking gradual steps to re-open Maraş.

But making improvements on that front is slow and painful. 1974 of course, represents a point in Turkey’s recent history when a window of opportunity opened up, and it became possible, through force of arms, to control more territory. Much of Erdoğan’s political project is geared towards positioning Turkey in anticipation that such moments will occur again. The Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict was an example of this.

Our Civilizational Cause (Medeniyet Davamız)

He’s beating the horse here, but this is Erbakan taking out another chapter to argue that his movement is also about rolling back the Westernization project that the Kemalists (and Young Turks before them) have unleashed on Turkey. He sees Westernization as civilizational treason and believes that it has caused immense cultural and social degeneration in an otherwise purse-hearted Muslim country.

It’s this sort of thing, page after page:

For two hundred years, foreign powers have tried to alienate our resolute nation from itself by destroying its national consciousness.

That's why we are against Westernism, which imitates the customs and traditions of Western countries and sees those countries as superior to our own country. Turkey cannot abandon its national identity and melt into Western countries. Our nation's structure and history are not suitable for this.

Luckily, salvation is at hand:

Yes, foreign views and imitative approaches have entered our body. But thankfully, these influences that entered us later did not take hold within us. Our body is solid. These effects are temporary. Our Milli Görüş [National Vision] is a suit that fits our nation. Foreign leftist visions, liberal visions, whatever visions, are akin to someone wearing someone else’s suit, with the arm sleeves too short, and pants at knee-length.

This kind of talk of course, is pretty standard for far-right movements across the world today. The idea is that problems arise because the nation is being forced into an unnatural position, et cetera.

The Kurdish question, for example, Erbakan writes, is purely the result of foreign thinking. I think the imaginary conversation below amounts to the most succinct explanation of the Islamist approach to this issue:

So here is what we say about this:

“Friend, you want to speak Kurdish, right?”

“Yes.”

“So tell me, what are you going to talk about?”

“Sir, I will talk about atheism and I will divide Turkey.”

Then, whether you speak Turkish or Kurdish, you are harmful.

“What are you going to talk about?”

“I will talk about Islamic brotherhood, our unity and solidarity.”

“Then you may speak Ugandan if you want, and I will kiss you on the forehead.”

The solution to this issue is not to establish a separate state or a separate federation. There can never be such a solution. Because that will neither bring happiness to our country, nor to humanity, nor to our brothers of Kurdish origin. All the Western states unite and become one state. Would it be right for us to fall for their games and divide between ourselves when they are uniting? They are playing this game to divide us, oppress us, and to swallow us all one by one. Nobody should be a pawn in this game. If our Kurdish brother in the South-East has to travel to Izmir, to Istanbul on a passport, who would be happy about such a thing!

You read reports by AK Party surrogates from the 2000s, as the country was getting into the peace process, and it’s basically more polite, liberalized versions of this.

It didn’t work of course, and the peace process broke down. And even though the Kurdish movement is moving away from leftist ideas, their voter base is still heavily against the state, most recently voting for opposition candidates across the country.

That’s it for now. The final part is coming tomorrow or Friday at the latest.

One thing I’ll say though is that even I was a little suprized at how tight the continuities are between Erbakan and the current Erdoğan regime. There are important differences as well though, and I’ll reflect on them in the last chapter, which in many ways is the most important.