Melville in Istanbul

The author of Moby Dick on Istanbul's dancing dervishes, beautiful faces and roaming dogs

When he wasn’t whaling or writing, Herman Melville, like the rest of us, enjoyed a little tourism. In 1856, he visited Istanbul for a week as part of a six-month Grand Tour that went from Europe through the Holy Land. Melville’s diary entries from the city may not be as profound as Moby Dick, and they’re certainly not as long. At times, they seem indistinguishable from many other travel accounts from the era, complete with the same observations, cliches and prejudices. But they also show something of the keen eye and literary flair that enabled Melville to turn a 500-page meditation on whales into the great American novel.

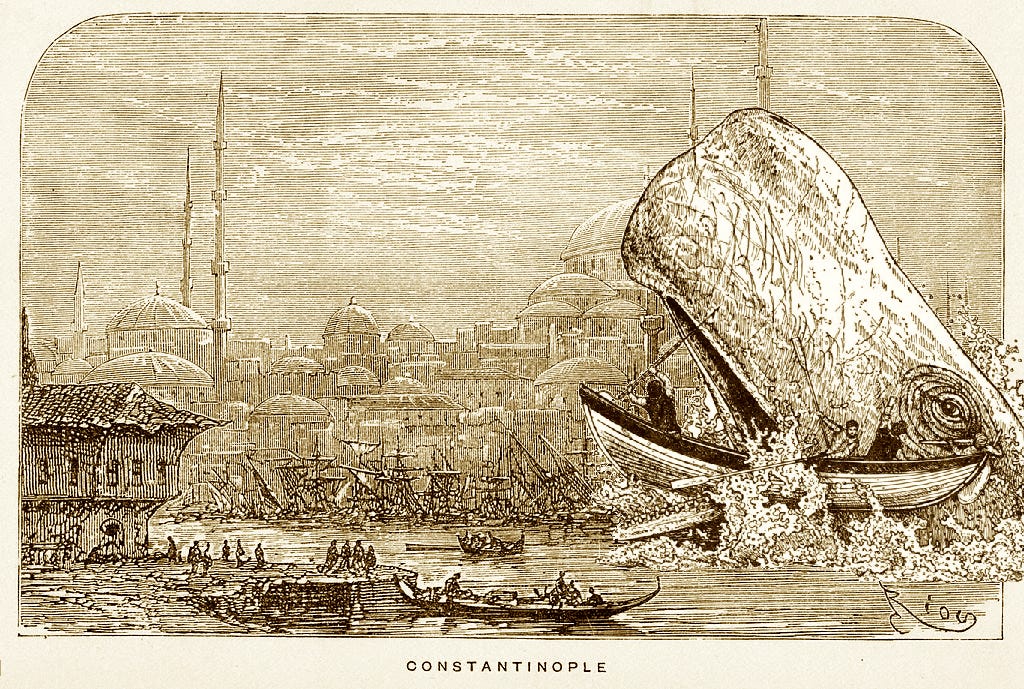

Well-read and well-travelled as he was, Melville certainly had an image of Turkey in his head before visiting. Indeed, the Ottoman Empire comes up more than you might expect in Moby Dick, providing a dozen or so metaphors over the course of the text. Captain Ahab is described as a sultan, and, waxing more literary, Melville writes that the “sultanism” of Ahab’s brain “became incarnate in an irresistible dictatorship.” Soft or calm waters are “Turkish-rugged” while a man calling out from the mast is like a “Turkish muezzin” in a minaret. Recognizing Moby Dick amidst the vastness of the ocean is like spotting “a white-bearded Mufti in the thronged thoroughfares of Constantinople.” In one extended passage Melville compares a male sperm whale surrounded by a school of females to “a luxurious Ottoman” in his harem.

More pointedly, Ahab’s relationship with the white whale is bookended by Turkish metaphors of violence. Describing how Moby Dick “reaped away Ahab’s leg,” Melville writes “No turbaned Turk, no hired Venetian or Malay, could have smote him with more seeming malice.” Then, when Ahab finally catches up with Moby Dick at the end of the book, his death [spoiler alert] comes again in Ottoman terms. Ahab harpoons the whale, but then the running harpoon line loops around his neck “and voicelessly as Turkish mutes bowstring their victim, he was shot out of the boat…”

Yet despite these unsavory similes, Melville’s actual impressions of Istanbul were more balanced. Sailing up the straights en route from Salonica, he seemed disappointed to note “Little difference in the aspect of the continents,” although “Asia looked sort of used up – superannuated.” When he commented on the thick fog to another passenger on his boat, the “Old Turk responded God's will is good & smoked his pipe in cheerful resignation."

Initially, Melville found Galata busy, bewildering and claustrophobic: “crowds, crowds, crowds.” His first night he opted to stay in his hotel: “Dangerous going out, owing to footpads & assassins. The curse of these places. Can't go out at night, & no place to go, if you could.” Later, he tried to visit the Galata Mevlevihane, but didn’t get there in time: “Too late for the Dancing Dervishes. Saw their convent. Reminded me of the shakers.”

At Ayasofya he was put off by a priest trying to sell him fallen mosaic tiles. Moreover, the thought the precious marble and stones lent it a “roman catholic air.” Sultanahmet mosque, by contrast, won high praise: “soaring up with its snowy spires into the pure blue sky. Nothing finer.” Visiting another mosque, Melville wrote ecumenically: “Off shoes & went in. This custom more sensible than taking off hat. Muddy shoes; but never muddy heads.”

On a trip up the Bosporus to Büyükdere, Melville was reminded of “the Highlands of the Hudson.” He was most impressed, however, by “the beauty of the human countenance,” specifically as manifest by the women he saw:

Singular these races so exceed ours in this respect. Out of every other window look faces (Jew, Greek, Armenian) which in England or America would be a cynosure in a ball room.

Elsewhere he noted the “beautiful faces” of the Greeks and "some very pretty women" in the harem of a “fine old effendi.” But despite this and a few other comments on the people he met, Melville once again seems most expansive when discussing animals. He devotes an entire paragraph to Istanbul’s dogs, which is worth quoting in full:

The dogs. Roam about in bands like prairie wolves. No masters. No Turk seems to have a dog. None domesticated. Nomadic. Against religion to kill them. Scavengers of the city. Terrible outcries at times. At night. Fighting of the dogs. Strange to come up on a pack of them in some lonely lane. Mostly yellow, with long sharp noses. Some much scarred, others mangey. See them lying amidst refuse, hardly tell them from it. Same color. See them over a dead horse on the beach.

Thankfully Melville ends his description here. But you get the feeling he could have continued for pages.