The Flag Poem

Baykar Teknoloji is apparently training pilots for its new Akıncı drone, the most powerful yet to join its arsenal. During a graduation ceremony for people qualified to operate the system, chief technology officer (and presidential son-in-law) Selçuk Bayraktar read a few lines from a poem everyone there probably knew by heart:

It’s commonly referred to as “the Flag poem”. Below is my translation, followed by a few paragraphs on its history and place in Turkish life today.

The Flag O white and scarlet ornament of the blue skies, My sister's wedding dress, my martyr's last cover, Bright o bright, wave upon wave is my flag! I have read your epic, I shall write your epic. I shall dig the grave of him, Who does not look upon you with my eye. I shall wreck the nest of the bird, That flies without a greeting to you. Where you fly, there is no fear nor sorrow... In your shadow, lend me, yes me, some space as well, What matter if the day doesn't dawn: The light of the crescent and star is enough for the homeland. On the day war took us to snowy mountains, We warmed in your scarlet, On the day we fell from mountains into deserts, We sheltered in your shade. O you purity, fluttering in the winds; The dove of peace, the hawk of war My flower blooming up high. I was born under you. I shall die under you. My history, my poem, my honor, my everything, Pick a surface among the surfaces of the earth! Wherever you want to be planted, Tell me, I shall plant you there!

Even by the standards of nationalistic verse, the Flag Poem isn’t particularly nuanced, but that’s what makes it so popular. It’s easy to understand, memorize and is appropriate for almost any formal occasion. Teachers and soldiers love it for those reasons.

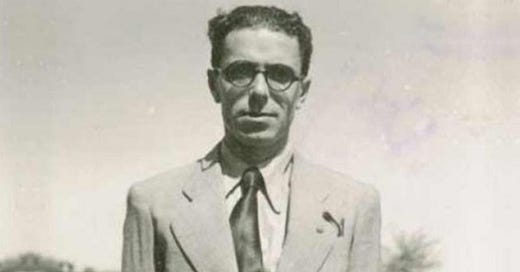

Its poet, Arif Nihat Asya, actually was a teacher in his home province of Adana in 1940. Every January 5, Adana celebrates the withdrawal of French and Armenian forces from the province in 1922, which involved (and still does) a giant flag being hoisted between the city’s clock tower and a mosque minaret. Asya was asked to find a student to recite a poem on that day. He picked a few students and sent them to the library, where they were to find a poem about the nation’s flag worthy of the occasion.

A few days later, the students told him that they couldn’t find one. He sent them back to look again, and again they were unsuccessful “What is to be done?” Asya said, recounting the story to Yavuz Bülent Bâkiler, “I said to myself, ‘Arif, you will write this poem!’” So the night of January the 4th, he literally burned the midnight oil. “As daylight broke, the Flag Poem was ready. It remained as I wrote it on that night. I didn’t fiddle with it a second time.”

He may not have edited the poem, but he certainly polished that origin story. It sets up this idea of an unexpected, yet devastating deficit in romantic flag poems, and Asya heroically steps in and fills the void once and for all. Really? Something along those lines may well have happened, but it’s a bit too stylized for me to believe outright. It feels a bit like a subtle extension of the world the poem depicts.

Either way, the poem came under criticism in Turkey’s brief liberal period in the late 2000s and early 2010s, mostly for its second stanza. I think the bit about destroying the nests of irreverent birds was a little too bellicose for a country in the EU accession process. School books first removed the offending stanza, then in 2014, the whole poem. Some teachers kept sneaking the poem back in, and there was briefly a bit of tension between teachers’ unions and offended parents.

I’m not sure if the Flag poem is officially back in the curriculum, but it certainly is in spirit. I googled around a bit and came across this teachers’ forum, discussing whether it was OK to assign. Nearly everyone on the forum praised the poem and encouraged teachers to use it. One user named “Alamet-i Farika” wrote in April of 2019 “The poem was banned, but I don’t think it would be a problem now, and I don’t think there is any possibility at all of there being a complaint.”

The poem wasn’t banned per se, but Alamet-i Farika is probably right in his/her assessment of the mood. I don’t think teachers need to worry when assigning the poem today. Irreverent birds beware.

Here are some of the ways in which the poem is recited today:

School recitals. This is where the poem really lives. This one from Hatay is really extravagant, filmed by drones.

There is a chorus version in the 2018 film Börü, a Hollywood-style depiction of how the 2016 coup attempt was thwarted. The piece was done by Lincoln Jaeger, who apparently works on film and video game music. It appears a bit towards the end of the film, where there’s a flashback to Atatürk, then scenes of the morning of July 16.

This is a very popular professional recital. In my very (very) brief period of military service, our superior officer insisted on a rising intonation in the second line of the fifth stanza (barışın güvercini, savaşın kartalı/the dove of peace, the hawk of war). I’m pretty sure this was wrong, and it weirdly upset me to hear it that way over and over again (everyone agreed with me, but we were all too chicken to say anything. Not the hill I’m dying on). Later I discovered the same mistake in this recording, so that must be why the officer insisted on it.

There is also this video of a few Gendarmerie Special Operations (JÖH) soldiers filming themselves as they’re hoisting the flag over a neighborhood during the 2015 anti-PKK military operations in the Southeastern provinces. One of the guys spontaneously breaks into the Flag poem, then finishes by shooting a few rounds into the air.