This week, I thought I’d pick out a few terms from Turkey’s political lexicon and explain them. I might do this from time to time, so feel free to let me know which ones you like, and what you’d like to see more of.

Mr. Kemal [Bay Kemal]: it may not seem like it from the direct translation, but this is Erdoğan’s nickname for Kılıçdaroğlu, akin to Trump calling Clinton “Crooked Hillary” in the 2016 presidential election. It’s pejorative in a very specific way. In Turkish, the formal way to address someone is to use their first name, then add “bey” or “hanım”. So the usual way to address Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu would be “Kemal bey”. If you want to be a little fancier and use his last name, you’d say “sayın Kılıçdaroğlu”, which roughly means “respected Kılıçdaroğlu”. That’s it. Those are your two options.

Now some people who were around at the hight of Kemalist reforms used to do is to adopt the Western way of addressing someone by their last name and adding the Turkish version of Mr./Mrs., making it Bay/bayan. The founder of Turkey’s most influential conglomerate, Vehbi Koç, for example, addressed a letter to his son “Bay Rahmi M. Koç”. It’s one of those linguistic innovations people tried at some point, but it didn’t catch on.

That’s why today, “Bay Kemal” has a slightly ridiculous ring to it. It sounds like a cartoon character, or something out of a dubbed American movie from the 1990s. Erdoğan constantly makes fun of Kılıçdaroğlu for losing elections but still clinging on to the CHP’s leadership. “Bay Kemal… is a timid, cowardly, wimpy, pathetic individual” Erdoğan once said. He himself of course, is a yiğit, the unbending, unyielding “tall man.” There’s nothing like a nickname to put someone down, and paint them as a contrast to yourself.

You were all there! [Ulan hepiniz ordaydınız be!]: this one takes some explaining.

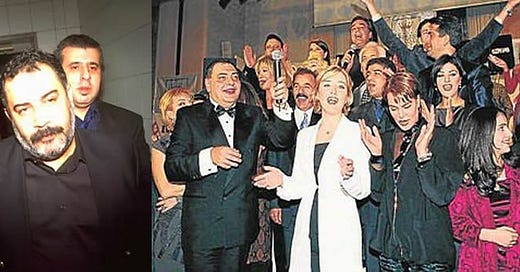

In 1999, the legendary musician Ahmet Kaya attended an event held by the Tabloid Journalists’ Association. The place was packed with some of the most famous artists and producers in the country at the time. Kaya received an award for best artist, and in his acceptance speech, he saluted the Saturday mothers and said that he was going to put out a song in Kurdish, and that there were producers in Turkey brave enough to back his venture. The mood shifted immediately in the hall, and soon people were singing nationalistic Turkish songs, boo’ing Kaya and throwing things at him.

It was awful. Kaya received death threats, had to leave the country, and soon died in self-imposed exile. He is remembered as one of the country’s greatest musicians in recent times.*

Now fast forward to 2013. Kemalism had taken a back seat, the Islamist AK Party government had been in power for more than a decade, and the Gezi park protests were rocking the country. In a bid to resolve the Kurdish issue, then-PM Erdoğan was also pursuing peace with the PKK.

In a parliamentary group meeting, Erdoğan said that the Kemalists had to pay for decades of oppression:

On that day in the award ceremony, as you know, they attacked Ahmet Kaya.

Who attacked him? It was those who attack us at Gezi park, they attacked Ahmet Kaya on that day!

[applause and shouting from the AK Party parliamentary group]

Now some of the artists who attacked Ahmet Kata on that day say “I was in the bathroom when that happened,” another says “I was outside when that happened.”

You were all there!

[shouting]

You were all there. You were all there.

We are watching you on those camera recordings, those can never be lost. We see you. The people see you. Be honest. The liar’s candle only burns until yatsı [the last prayer of the day, usually before bed]. Your candle has now gone out. We see all of you.

Sometimes words catch thunder. Erdoğan has been able to do that a few times in his career, and that was definitely one of those times.

Gezi marked a moral inflection point. It completed Erdoğan’s transition from oppressed to oppressor, revolutionary to riot police. It also brought together the progressive left (the Ahmet Kaya crowd) and the Kemalists (the people who boo’d him away). Erdoğan didn’t want the Kemalists to be absolved by the Gezi protests. They were rising to political heaven as he was falling down the other way, and this was him, grabbing them by the collar as they met midway, pulling them back down.

And to be clear, “you were all there” is a very imperfect translation. It’s “ulan hepiniz ordaydınız be!” with the first and last words being practically untranslatable into contemporary English. They are colloquialisms that give the statement greater velocity. You just know those words weren’t on the prompter he was reading from. It’s that extra emphasis that gave the phrase its wings.

A person whose forehead touches down in prostration [alnı secdeye giden kişi]: some years ago, I asked my great-uncle what he’d do if he was my age. He gave me a razor-sharp look, then said “I’d make sure I don’t miss any of my prayers.” That’s a man whose forehead touches the ground. Five. Times. A day. (No, he was not impressed by my forehead.)

In political settings, the phrase is a not-so discreet way of indicating that a person is religious. So if a couple of AK Party politicians are weighing candidates for deputy prime minister, they might say something like “Ahmet bey would work well with us. Plus, he is someone whose forehead touches down in prostration.”

The phrase used to be an unambiguously positive in conservative circles. I’d say that has changed in the recent decade or so. Some of that has to do with the Gülenists. It was used for them in their heyday, so much so that it was almost a euphemism just for them (pre-2013, when the great Erdoğan-Gülen Schism happened). The Gülenists are now universally reviled, so the phrase has taken a hit. More than that though, the tendency to equate piety with morality is fading, even among conservatives. Ask the average person on the street what he thinks of when he hears the phrase “someone whose forehead goes down in prostration”, and he’ll probably say it makes him think of corrupt officials.

That’s why the below sokak röportajı went viral last week. The person says “praise be god I am muslim. If my president steals - Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, even if he steals - does his forehead go down in prostration? It does. I mean, does he pray five times a day? He does.” He was suggesting that it was acceptable for a person (in power) to steal as long as he is religious. That contrast between theft and prostration is why such videos go viral these days. People suspect that one acts as cover for the other.

*See here for an excellent English language introduction to Ahmet Kaya