I haven’t written a “Language of New Turkey” post in a good while. This is a series in which I take on some terms of phrases in Turkish popular discourse and break them down.

This time, I thought I’d take some of the phrases popular in the Turkish opposition.

Kurtuluş yok/tek başına [there is no liberation/on your own]

This is the start of a chant of the Turkish left that’s been heard very widely across the Turkish opposition since İmamoğlu’s arrest. It’s a bit hard to translate in full, but here’s my best attempt:

There is no liberation

On your own

Either all together

Or none at all.

Here it is at some recent protests:

The slogan is inspired by a poem of the German leftist Berthold Brecht (who happens to be one of my favorites growing up) entitled “Keiner oder alle” [All of us or none], specifically the refrain:

Everything or nothing. All of us or none.

One alone his lot can’t better,

Choose the gun or fetter.

Everything or nothing. All of us or none.

The Turkish slogan is based on a 1972 translation, this of course, being the decade when the Turkish left was on the ascendent. I’m not sure when the translation transformed into a slogan though. It might have happened right away, in the following decades. Do tell me if you know.

Either way, I think it’s notable here that the Turkish left has a particular cadence to the way they shout their slogans. The beats are often 2-2-5-5, which creates this sense of a building force. Let me break it down:

Kurtuluş, yok! [there is no liberation]

This is two beats, so it becomes “Kurtuluuuş—yok!”

Tek başına! [on your own]

Again two beats, so it goes “tekbaaşııııı—na!”

Ya hep beraber [either all together]

Five beats this time, so a staccato “Ya—hep—be—ra—ber!”

Ya hiç birimiz [or none of us]

Again five beats, “ya—hiç—bi—ri—miz!”

This pattern — short declarative bursts followed by rhythmic, choral affirmations — is widespread in leftist chants in general I think. In Turkey though, the way the slogans sound is almost iconic. Turkish also lends itself well to this nasal staccato, and the rising and falling tones.

Here’s what it sounds like at a march of the Union of Chambers of Turkish architects and Engineers (TMMOB, which I discussed here a bit), ten years ago:

Here it is at an İmamoğlu rally a few months ago:

Or at at a DİSK, one of Turkey’s major labor unions, chanting the slogan last year, or students at ODTÜ chanting it in 2012.

Here again, on the cover of the satirical magazine Leman, probably drawn right between the cancellation of Ekrem İmamoğlu’s diploma and his arrest:

For more on the slogan, and its transition from German into Turkish, read Volkan Çıdam’s essay here.

Çökme operasyonu [Dispossession operations]

Again, this is pretty difficult to translate. In Turkish, the root verb “çök-” means to collapse. A building that has collapsed is said to have “çöktü.” When you drink Turkish coffee and the grounds have settled at the bottom, they are also said to have “dibe çöktü.” Or in the countryside, if someone points to the ground and says “çök,” they’re using the imperative to tell you to sit or squat.

For the most part, it’s a pretty warm, earthy, Turkic-sounding word. But there is a more salient use of the term these days, and it’s political, and it’s less warm.

There is the expression “mala/mülke çökmek,” literally “to collapse on property,” often abbreviated as simply “çökmek.” It’s most often used to express the act of one person or group appropriating the property of another. This is usually the kind of theft that’s accompanied by a broader political takeover.

When revisionist historians talk about events that involve the expropriation of non-Muslims in Turkey’s history, including during the 1915 Armenian genocide, or the 1942 wealth tax on Greeks and Jews, they are talking about what in more colloquial moments, will be referred to as “çökmek.” Many of the biggest industrialists of the Republican era, including most prominently the Koç and Sabancı, are said to have gotten their start by taking advantage of these periods of “çökme” wherein they were able to acquire formerly non-Muslim capital on the cheap.

To me, this kind of political “çökme” invokes the image of an airborne predator descending on its prey, absorbing it, and growing stronger. The act is silent, inevitable, and evil.

It is also by no means specific to Turkey. Not for nothing were the Guilded Age industrials called “robber barons.” The United States’ westward expansion, European colonialism, Zionism, and many other chapters of history, can all be seen as acts of “çökme” by this standard. There’s a variety of political theories about how state-building has its origins in banditry. “Çökmek” would very much include those events, but the Turkish left is understandably more specific when talking about Turkish history, so it mostly gets applied mostly instances in which Sunni Turks descend on “gavur malı,” or the property of the non-Muslim infidels.

In political discourse today, this term is used broadly to talk about the Erdoğan regime’s treatment of public property as well as their political enemies. It’s often phrased as a “çökme operasyonu” in opposition speak.

The liquidation of Fetullah Gülen’s global empire is often referred to in this way, as are large construction projects, especially if they’re re-zoning designated wildlife areas. Note that these are radically different types of endeavors. One involves designating a specific group of people as enemies, stripping them of their property, and re-distributing it as rent among one’s own supporters. The other is good old fashioned re-zoning to build mines, tourist resorts, and other money making schemes on land that was previously protected.

In essence, contemporary “çökme” operations are about plucking some valuable thing that has developed over years (and sometimes centuries) and cashing in on it. The valuable things in Turkey — as in any country — are often in the public domain. That’s why it really helps to have absolute power over the state in order to “descend” on all of them. Sometimes it’s a tricky thing to do of course.

İsmail Saymaz had a piece out in January entitled “Boğaziçi’ne çökme operasyonu” in which he described how the regime was violating the independence of Boğaziçi, one of the country’s most prestigious universities, especially in the humanities. Here the term implied that a certain intellectual, reputational, and institutional capital had been built up at this university, and that the new regime was now “descending” on that to appropriate it for the new elite. Calling this a “çökme” operation implies that the new elite would benefit from having occupied this institution, but it also hints that this will ultimately degrade the qualities that make Boğaziçi desirable in the first place.

I also think that the term “çökme” implies a continuation between historical treatments of non-Muslims and the Erdoğan regime’s treatment of the opposition today. Increasingly, the argument many in the opposition make is that this isn’t merely state repression, but the actions of a victorious army seizing the territory of vanquished enemies. Here is a CHP parliamentarian reacting to the arrest of Istanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu:

The AKP tries to forcibly seize control [çökme] of any municipality where it cannot win, where it cannot gain the people's consent. This is what we call a seizure operation [çökme operasyonu] — an usurpation of the people’s will, an act of tyranny. There is no other word for it.

This tyranny also entails looting, plunder, the destruction of public resources, and the funneling of what belongs to the people into the hands of the AKP’s cronies. This, in essence, is what the practice of appointing trustees [kayyum] entails.

More on the İmamoğlu arrest in the next topic.

The radish analogy

If you’ve been following Turkish politics, you might have noted that there’s been some talk of radishes lately. As so often the case, this is an analogy that has developed in the rhetorical ping-pong match between regime and opposition.

It’s based on the saying “Turpun büyüğü heybede,” literally meaning “the bigger of the radishes is still in the saddlebag.” I’m not sure about its exact origins, but the phrase first gained mainstream prominence when Süleyman Demirel, one of the great center-right statesmen in Republican history, used it many decades ago.

Here it is, as relayed by the columnist Rahmi Turan:

In a market in Aydın, a villager was selling radishes. When customers came by, he would display the small radishes.

One man came along, looked, and said:

"These are small." He frowned and walked away...

The villager called out after him:

"Hey, wait, fellow, wait... the big radish is still in the saddlebag!"

I find that the journalists who relay this story aren’t very good at interpreting it. They seem to think that Demirel was hinting at deep state forces, or that the biggest problems are hidden from sight. I doubt that. Demirel was an engineer and started his career as an economic planner. The story itself is about hoarding, inventory speculation, or “price gouging” to use the retro phrase. He probably used the phrase to say that a country’s potential is squandered when it is governed badly, or simply that a bigger thing is to follow, like “this is only the tip of the iceberg.”

Either way, it still sounds light-hearted when it comes from Demirel. With Erdoğan, the phrase has taken on a darker meaning.

When Beşiktaş mayor Rıza Akpolat was arrested on bogus charges in January of this year, it triggered a lot of protest among opposition. The regime had lost big in the major cities, and it was taking by force what it couldn’t at the ballot box.

Reacting to this sentiment, Erdoğan doubled down, saying that the opposition was corrupt, and would be fully exposed soon:

The big radishes are still in the saddlebag, and haven’t been spilled out yet. When those big radishes are finally laid bare, these people won’t even have the face to look their own relatives in the eye — let alone the public.

This was widely interpreted to mean that Erdoğan was preparing to have Istanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu arrested. I think the radish analogy was just about obtuse enough for Erdoğan to claim that these arrests were the result of independent investigations, but clear enough to sound as a threat. That’s why these things quickly become shorthand in Turkey, while just about allowing foreign states and international banks to maintain the pretense of a rule of law.

The opposition seized on the analogy. While holding a rally in Trabzon, someone in the crowd actually handed İmamoğlu a radish. He took it, and said “look president, the citizen is showing you the bigger of the radishes,” then saying as an aside “he [Erdoğan] says he’s got a big one in his pouch.” I read this as a way of refusing compliance with whatever demands Erdoğan must have made on him.

Erdoğan usually does what he says he’s going to do. He soon had İmamoğlu arrested, and his people levied charges of corruption and terrorism against him. I think it’s fair to say that the charges were wholly unconvincing.

But the analogy continued.

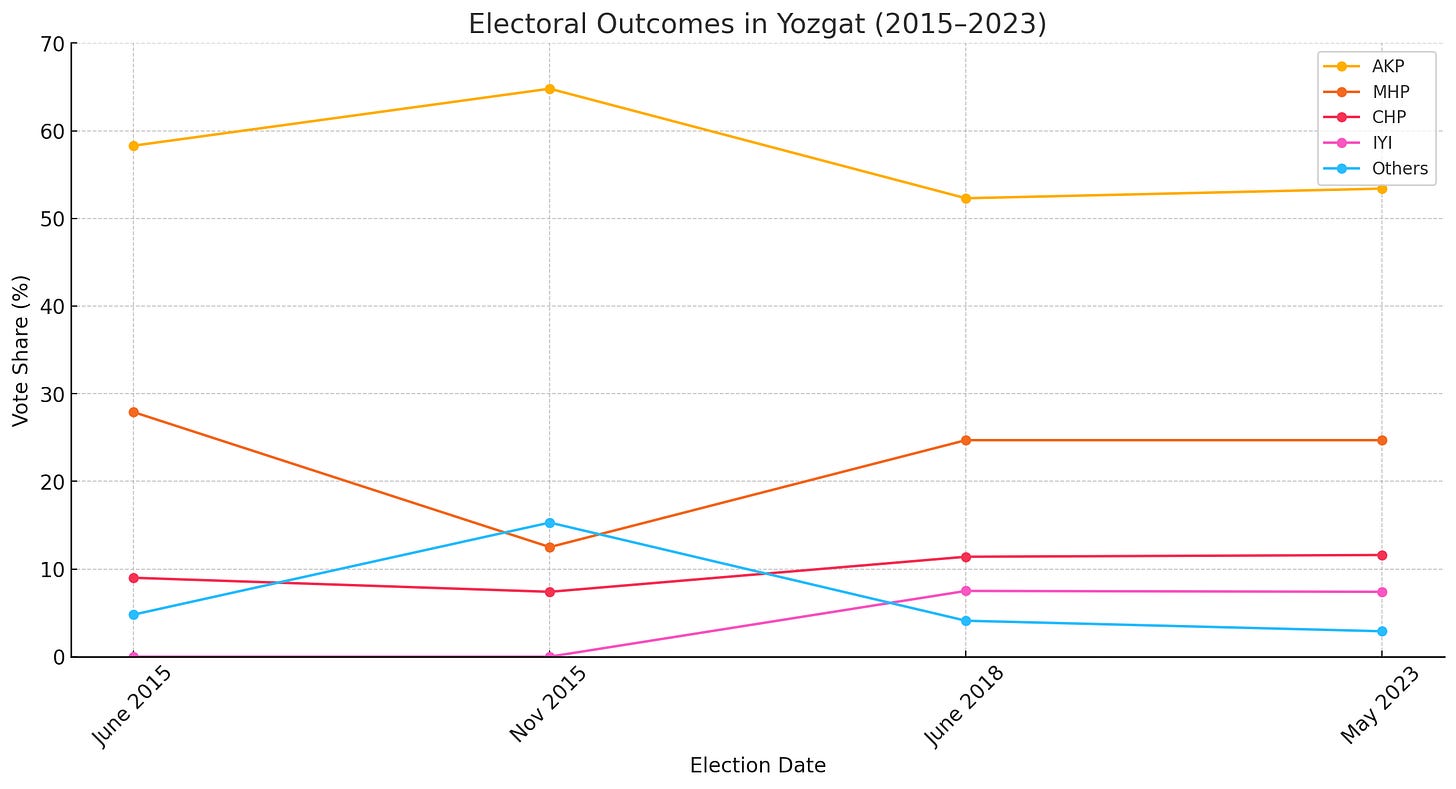

As most of you know, the CHP held huge protests in the wake of the Istanbul arrests, first in Istanbul, but then across the country as well. Amazingly, the first one was in Yozgat. This was shocking because it’s very deep Erdoğan territory. The AK Party and MHP get 70-80 percent of the vote in Yozgat::

But turnout was huge. Yozgat’s farmers had been hurting badly for a long time, and said that they were willing to break from the Erdoğan palace. Many formed a convoy of tractors and spoke at the CHP rally. The event was especially remembered for the words of the farmer Abdullah Ceylan, who took the stage to speak:

I speak to you as a farmer who stands as an example, who demands his rights, who doesn’t let his rights be trampled on. We want justice and democracy. As farmers, we will not allow corruption, unlawfulness, or injustice

…

I thank the President of the Republican People’s Party (CHP), Özgür Özel, and our presidential candidate Ekrem İmamoğlu. We will not leave him in jail, we will not give up, we will be free!

We are coming to power. I’m giving this speech as a farmer. They fined me one million lira [for the tractor convoy, but that’s in old-Turkey currency, so a thousand lira]. If you don’t fine me a hundred million more, you’re cowards!

I’m speaking here to the farmers who don’t stand up for their rights. To those who don’t keep track of what their goods are worth. If this system continues like this, we will not be able to escape hunger, misery, and incompetence.

We will tear this system down, we will tear it down, we will tear it down!

Let me give some advice—just this. One does not govern a state with turnips and şalgam [fermented carrot juice], one governs with justice! With law—and we will hold them accountable when the time comes. I am a farmer, a farmer. A farmer who works for justice, who works for the people. I promise you—it will be beautiful, it will be beautiful, it will be beautiful. I greet you all with respect and love.

That last bit got a lot of play, and people especially noted the man’s accent. He didn’t really say “with turnips and with şalgam” [turp ile, şalgam ile] the way one might in Istanbul Turkish, but but speaking with a deep inner Anatolian accent, said “turpunan, şalgamınan.” That was a unique moment, in a way that the CHP later couldn’t reproduce. This farmer wouldn’t have dared to call out Erdoğan directly, but the analogy provided just enough of a rhetorical cover for him to get his point across: the president was the problem.

The opposition internet quickly created all kinds of memes

The Yozgat rally, and especially the words of Abdullah Ceylan, stood out because they meant that the CHP’s power wasn’t confined to the big cities — it could reach deep into the strongholds of the AK Party as well. I think that’s why the palace has been ramping up its repression. They want to make sure that the “trup-şalgam” moment remains a weird one-off, and that the fusion between city CHP-types and farmers doesn’t take hold.

Anyways, that’s it for this post. I leave you with the Einheitsfrontlied, another song that came out of the poems Brecht composed while in exile in Denmark:

I always enjoy these language pieces but this one was particularly interesting. I don't want every single one of my comments to be comparisons to be Britain, but I was really struck by the contrast between the Yozgat farmer's appeal to his community's self-interest on the basis of a higher principle, and the ugly language and ideas of the recent farmers protests we had in the UK regarding the introduction of an inheritance tax for agricultural land: https://youtube.com/shorts/330rDBf58Jo?si=-n21ZsHLdE1CujZy

For all Turkey's problems, it does seem from the outside there is a real core of the population, that despite their many different views and interests, engages with political arguments as citizens in a constitutional system. I'm sure Turkish policies is far messier on the inside on a normal day but it is clearly a much more pluralist political culture than eg Russia ever has been, or eg Hungary today.

Anglo or Western politics really seems to have lost this type of sophistication. Despite being frustrated, the public is passive, and the political system doesn't have an outlet for reaching out beyond either the small minorities of key swing voters or hyper engaged partisans. It is almost that the bizarre thing is so many discontened people are continuing to vote for established parties rather than choosing something new and risky.

If Turkey is at the 'highest stage of resentful authoritarianism' then this reaction to Ekrem's imprisonment would seem to suggest what the answer to that stage is. It's not more focus groups or slightly cheesier ads or slightly better turnout on election day, but encouraging the public to take responsibility for the political system they live in. It's only by taking ownership of the problems a society faces and trying to solve them that citizens can practice democratic self-government, which is surely the only alternative to both bully power and these paralysed liberal bureaucracies that don't even understand their own decaying legitimacy.