Last week, Britain celebrated the “platinum jubilee” of Queen Elizabeth II. This week, Belgium’s King Phillipe begins his visit to the Democratic Republic of Congo, a former colony of his country.

When I read those news, I sometimes imagine what it would have been like if the Ottoman empire had continued as a constitutional monarchy. The Ottoman Sultan would still sit in Dolmabahçe palace and there would probably be a parliament in Istanbul. Turkey might have looked different on the map. Would it be a smaller country? Would it be larger, perhaps reclaiming some of its imperial borders? Would the monarch be an unpopular Westernizer like the Iranian Shah, or a conservative like Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud (a mere arriviste by comparison)?

Such musing has been unusual for recent generations because the Kemalist revolution had an exceedingly clear answer: things would have been infinitely worse with the Sultans. The Empire had to go. The Republic was the only conceivable way forward for the Turkish nation.

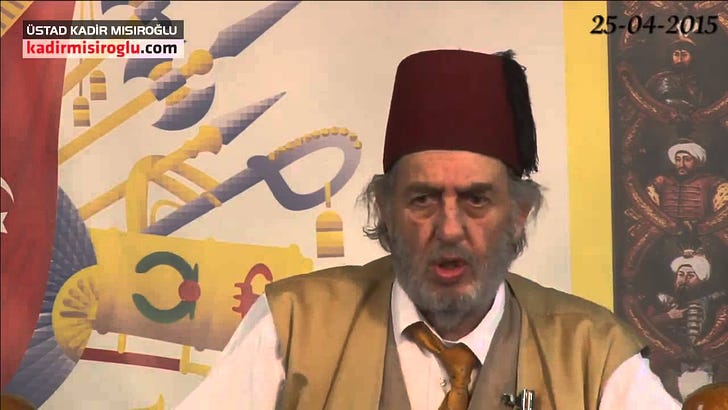

Some begged to differ, and they laid the foundations of what is now “New Turkey.” I have written about Necip Fazıl Kısakürek here, who wrote the book on Abdülhamit II (the basis for the TRT series). Another prominent monarchist was Kadir Mısıroğlu, an eccentric writer and polemicist. Mısıroğlu nourished a bitter hatred of the Kemalist regime and wrote historical tracts undermining its legitimacy. His 1965 book on the treaty of Lausanne lays the basis of Turkish irredentism, including the Erdoğan government’s claims in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Mısıroğlu stood out for using a cane and wearing a fez throughout most of his adult life. The cane, he said, was from the rheumatism he developed when he was in jail after the 1960 coup.* The fez was a symbol of his refusal to be a Kemalist, as well as a mark of distinction from the gavur of the Western world. Mısıroğlu’s citizenship was revoked after the 1980 coup, and he spent many years in exile in Germany and England, both of which he despised. Mısıroğlu was allowed to return to Turkey in 1991, and to his great pleasure, saw the rise of the AK Party in the 2000s, and the conservative awakening that it brought about.

In his later years, Mısıroğlu was known for holding long lectures to packed audiences every Saturday, and these were published at length on YouTube. His staff would collect questions, and he would respond to them at length, often weaving together personal anecdote, historical events and conspiracy theories. As with most such figures, Mısıroğlu was unabashedly anti-Semitic. He believed that Muslims were superior to non-Muslims, and had lost their geopolitical dominance because they lost sight of their civilization’s core values.

Erdoğan visited Mısıroğlu in hospital in 2018, but did not go to his funeral when he died in 2019. The problem was Mısıroğlu’s last will. He had famously said that “nobody who feels even the slightest bit of affection for Mustafa Kemal must come to my funeral.” This probably made it a bit too toxic for Erdoğan to attend, but many AK Party leaders did, as did Erdoğan’s younger son Bilal. The president had to restrict himself to a dry tweet. His political role demanded that he curtail his radical anti-Kemalism.

Below, I have translated a few minutes from one of Mısıroğlu’s YouTube videos. A tip of the hat here to the historian İlker Aytürk, who tweeted about this last year (for more context on the Turkish far-right, read his excellent paper here).

In his tweet, Aytürk calls this bit “The Sun Religion Theory ”, which (delightfully) is a play on “The Sun Language Theory” of the early Kemalist period. In summary, Mısıroğlu’s likens the Kemalist period to a solar eclipse. Islamism is the sun, Kemalism is the moon obstructing it. Turkey was at the darkest point in the early Republic, and has since been recovering more and more sunlight. (An analogous sun analogy comes to mind) He then flows into a series of other metaphors to flesh out the idea.

Mısıroğlu was a very colorful speaker and made a point of using Ottoman terminology, which can actually be enjoyable to listen to and translate.

Below is the video, as well as my translation from a section of it, starting around 8:20 minutes in. I have lightly edited Mısıroğlu’s words for clarity:

Since 1950, I tell you, our sun has begun to come out. The eclipse took about 100 years. 1839 - 1939.

The sun was entirely obscured until [19]50.

When there is a solar eclipse, it stays dark for five minutes, then the sun begins to come out again. Consider 1939-1950 as the time of full eclipse. In 50, the opening begins.

The first hero of this opening is Menderes. Its second hero is Demirel. Its third hero is Özal. Its fourth hero is Tayyip bey.

Of these, every one is more solid than the one before. Every one makes fewer mistakes than the one before.

We saw Demirel in a mosque despite him being a Freemason. We did not see Menderes in a mosque. I have met Menderes many times, and I never once saw him in a mosque, at Friday [prayers], at bayram, or at a funeral. But Demirel parked his Mercedes in front of Hacıbayram [mosque] and prayed the Friday prayer.

Özal, in the seat of the president, had Mawlid prayers recited and had the tarawah prayer recited with khatm. He assembled the khafiz [there are all non-mandatory forms of Islamic prayer that especially pious people perform. A Khafiz is a person who can recite the Quran from memory].

These things had been made into a big deal when Erbakan did them.

Tayyip bey has done more than the three combined.

What does this show us? It shows us a retreat in the enemy ranks, and an improvement and abundance among those representing Islam. It is the stage of lessening mistakes. This shows us fate. Fate!

It’s akin to how now, as we are approaching summer, it is getting warmer. If it had been fall, this progression would have been towards the cold.

When there is a cold day in between, we aren’t worried because it is against the essence of the season.

Seasons of transition contain contrasts.

Turkey is in the season of transition from kufr [disbelief, or denial of faith] to iman [faith]. You will see the time when this progression has reached its perfect state. But to earn the thawab [merit] you get from one step in this time, you will have to take a thousand steps at that time. Don’t forget: the little bit of goodness in times of deprivation is more important than a lot of goodness in times of plenty.

A little deed in the way of god today is of greater benefit to you than a great deed at the time of Islam’s victory. These days will pass. Have something written in your registers. Put something into the sack during your youth, [take advantage of] the vitality of youth, as well as the disorder of conditions and fallen nature, the pandemonium of the times. It is easy for a foot to slip and it is easy for it to straighten. Because the uprising [Muasara], the danger, isn’t over yet, it is a more auspicious time than the time when things will have straightened out.

God decides the times each person lives in, it isn’t up to anyone themselves. If you were young 50 years ago, there wasn’t anything you could have done. If you had advanced just a bit, they would have hung you. If you go 50 years forward in time, you won’t find anyone to straighten out. Everyone has been straightened out already.

Things are not like that today. Today you will encounter an unending number of people to straighten out.

Consider Vehbi Koç.

If you now tell him, “I worked in Germany, I have earned 100,000 Marks, but I don’t know how to use it. You are a man beneficial to the country, I will give this money to you and you put it to use,” he would send you away, wouldn’t he?

But say he has gone bankrupt. Then, if you take 10,000 Marks to him, he would take it, he would cry and think “there are still people who know to appreciate me.”

[smacks the table with both fists]

This religion of Muhammad - no inappropriate analogy intended [la teşbih vela temsil] - is like a rich man gone bankrupt!

[keeps smacking the table]

Helping it today does not compare to helping it when it has already acquired its former wealth and splendor!

May god grant us plenty of such days, and the good deeds and jihad and beneficence that follow from such days.

As is usual with such circles, his followers often ascribed keramet, or supernatural power, to Misiroglu’s words. He insisted that this was not the case, that he was doing “what the Frenks call futurism” and that his opinions were based on his careful study of cause and effect.

I’m always fascinated by is the mathematical calculation of merit (sevap). It’s an unquantified point system for Islamists, much in the way it still is for Christians (some denominations more than others). You know that every good and evil deed is of different weight in the eyes of god, and you constantly wonder about your ledger. The more literally you imagine this, the higher the level of uncertainty becomes, and the more anxious you get. Effective speakers like Mısıroğlu know how to leverage this feeling for political action. His theory here gives his (predominantly young) audience a historical context within which they can weigh the merit they can get from political action. Its optimism creates momentum and makes listeners feel like they are part of a great historical process - perhaps the great historical process.

It’s teleological of course. He has faith in Islamic supremacy, which conditions him to deduce Islamist ascendency. I’m not sure how he would have explained Turkish society’s increasing secularization, or the Erdoğan government’s rapid decline in popularity today. Would he have considered it a cold day in spring? Or would he be more worried by now?

* Mısıroğlu also claimed that there have been four assassination attempts against him, and that he was shot in the leg in one of these, that the tendon from that wound hadn’t healed, and that’s why he was using a cane. I think he also liked the cane because it made him look a little more like Abdülhamit II. He knew the value of having an alamet-i farika, or a brand, as one might say, and clung to it for that reason, if for nothing else.