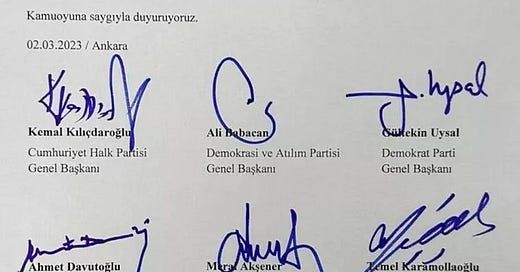

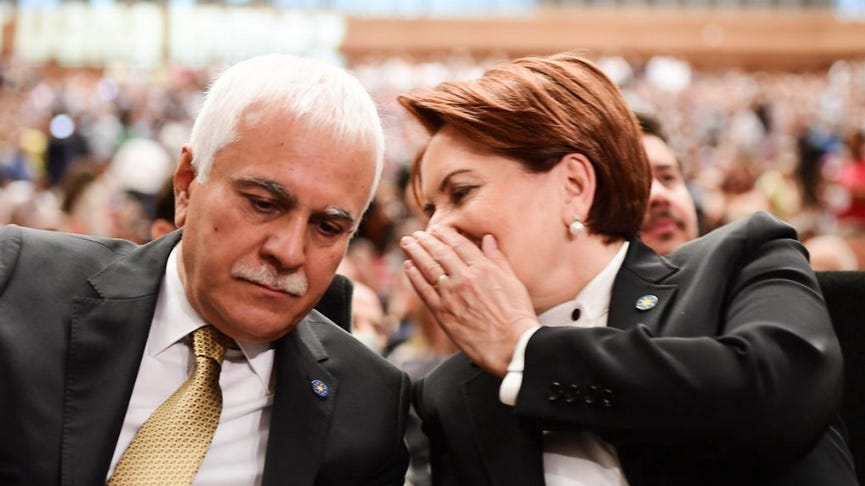

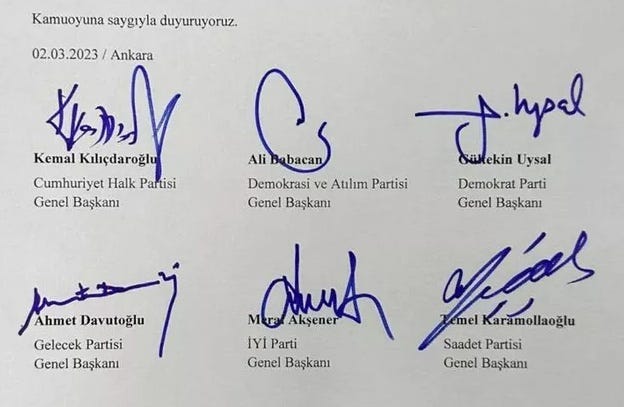

Ankara has been going through a very intense four days. On Friday, İYİ Party leader Meral Akşener made a bitter speech and effectively left the opposition coalition. On Monday, she was back, signing the agreement and ratifying CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu as the opposition candidate for the presidency.

The weekend in between was quite an ordeal. The opposition plane had taken a nosedive, its passengers floating around in zero gravity, their belongings strewn about.

We are now back - more or less - on the programmed flight path. In this pieces though, I’d like to take a look at those three days of pandemonium.

Turkey’s opposition commentariat put forward a lot of interesting ideas (at high velocity) over the weekend. Below, I have grouped the worthwhile arguments into three mutually inclusive categories.

Personal: Akşener, the argument goes, has a history of making rash decisions and being a difficult ally. Yıldıray Oğur was most comprehensive in presenting this argument, listing how Akşener was an ardent Tansu Çiller supporter, then collected signatures against her; she was involved with the AK Party’s formation, but withdrew last minute without explanation; she supported Devlet Bahçeli in the MHP, then rebelled against him after the 2015 elections; she formed the opposition İYİ Party, but objected to Kılıçdaroğlu when he wanted to put up Abdullah Gül as a united opposition candidate against Erdoğan in 2018.

Technical: this is the “kazanacak aday” (winning candidate) argument. Polls have consistently shown that İstanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu and Ankara mayor Mansur Yavaş were the most popular candidates against president Erdoğan. If you have two candidates who are almost certain to win, İYİ has argued, why go with Kılıçdaroğlu? For all his virtues, the CHP’s leader is a terrible retail politician and has looser stink all over him. And if Yavaş is too hard a right-wing figure for the CHP and HDP, there is always İmamoğlu. It never made sense to İYİ, and when it came time to approve Kılıçdaroğlu, they lost it.

Structural: despite its best efforts, İYİ is an Ülkücü party. Students of modern Turkish history will know that such parties don’t restrict themselves to representative politics, they are connected to a network of the state security apparatus, organized crime, and industrial interests (primarily in construction and manufacturing). That network is currently in symbiotic relationship with the Erdoğan palace. People like Ümit Özdağ are linked to the same network, and were confident in predicting that Akşener was going to leave the table. Some people therefore argued that Akşener probably stormed off on Friday under the influence of that network. There are two subgroups to this argument:

Kılıçdaroğlu increasingly wants a “hard transition” after elections. This means a clearly leftist agenda and a hard push against the Erdoğan-era capital that has built up, mostly represented by the “gang of five” construction magnates (actually much broader than five). İYİ, the argument goes, advocates for a “soft transition” in which the security bureaucracy, as well as much of the capital structure of the recent decades would remain untouched. This is a source of deep disagreement that has percolated up, created pressure, and burst open the coalition on Friday.

The state network fears a CHP-HDP connection, which could break the cordon sanitaire against the HDP, and thus undermine the national structure. Those making this argument will point out that in right-wing circles, talk of “radical leftists” is code for Alevis.

I can’t rule out any one of these. I think reasonable people can disagree about how to weigh them.

(1) has merit, but is obviously insufficient. Akşener has been known to be mercurial, but she was channeling displeasure that had been building up within her party. The main opposition media claims that there was a wave of resignations from İYİ, but I think that was exaggerated. The majority of the party structure didn’t have a problem backing Akşener, but its more astute strategists were worried.

I think (1) helps to explain the lack of planning and strategy. Akşener didn’t have a well thought-out strategy and left on an impulse. Over the weekend, she was forced to evaluate alternatives (no doubt thinking about the 7% vote she received in the 2018 presidential elections) and decided against a similar ordeal. I think (1) is gaining greater weight among İYİ members, especially now that Akşener is back at the table.

(2) is the argument that the İYİ Party has incessantly aired for the past year or so. It’s certainly what people within the party have been telling me for months. This is much of the steam in the pressure cooker.

On the other hand, if (2) was the only reason for Akşener’s sudden departure, it would have looked different. Kemal Can has argued persuasively that if İYİ actually had a technical concern, Akşener could simply have said something like “sorry, I’m not convinced on Kılıçdaroğlu as a candidate” and withdraw politely from the table of six. Instead, she said that the table “has lost its ability to represent the will of the people.” That’s the language of the Erdoğan palace. Figures on the political right, no matter their electoral reach, always imply that they represent “real Turkey.” This election, of course, is partly about proving that notion wrong. The collective opposition’s plan implies that lefties and liberals (sometimes called “whites,” especially this weekend) are at least as “real” a part of this country as the Ülkücü or İslamist.

So (2) is simplistic in making a technical point. There is a real divergence of viewpoints. The Turkish right, including the Ülkücü in İYİ, truly feel that it doesn’t make sense to think about the issue in policy terms. For them, politics is mostly a PR effort. It’s about connecting to the masses through a great “boss” figure. Once you’re in government, you call in the booksmart people - economists, engineers, scientists - and tell them to go about their business. If the global consensus is free-market economics, that’s what you do, and if it’s state planning, that’s fine too. That’s it. Oh, and you don’t steal. Bad things happen when you steal, at least when you steal too much.

That’s why (3) sounds outlandish to them. They’ll go along with a left-wing agenda to some extent, but will be uncomfortable when it eats into the electoral calculus in (2) and the incessant daydreaming about power and wealth.

So what about (3)? I’m more sympathetic to (3a) than (3b) as a causal factor. In my humble experience, being part of the opposition means that you’re constantly daydreaming about what you’re going to do when you’re in power. We’re now in a place in the political cycle where the daydreams are clashing, and they don’t clash on paper or rhetoric, they clash over appointments. People involved in these processes know that the “soft” vs. “hard” transition isn’t a matter that will be decided in the abstract (i.e. policy papers) but in the people who are actually involved in a potential new president’s inner circle.

A Yavaş victory would be immensely lucrative for people like Koray Aydın, and I’m sure that there’s plenty of people in İYİ who imagine that sort of thing in detail, and clung to the hope that it would come to pass. They’re upset that it won’t, which accounts for a great deal of the bitterness in Akşener’s voice.

(3b) is always going to be a factor, and I’d expect at this point that the Erdoğan palace would be pushing it especially hard. I think of it as a corrosive effect rather than something that would create a sharp departure that we saw on Friday.

To sum up, I think (2) and (3a) prepared the conditions for the departure, and (1) set it off. I think this is going to have consequences for the election campaign and possibly, a Kılıçdaroğlu government in the future.