There are a variety of terms in Turkish to describe political incumbency. I’m going to go through a few of them in this post. I think looking at these a little closer can tell us about the political moment we’re in today, especially as things are ramping up for election season.

Let’s cover the basics first: the term for government in Turkish is “hükümet.” One might speak of the “AK Parti hükümeti” in Ankara, or “Macron’un hükümeti” in Paris or “Çin hükümeti” for the Chinese government in Beijing. The word comes from the Arabic حَكَم (hukm) meaning to govern. Its root means to adjudicate. That's why a judge in Turkish is a “hakim.”

The term “iktidar” also refers to a government, but can be used to talk about a broader power structure. The word comes from the Arabic قدر, (qadr), meaning power. I'm no expert on this, but qadr might be comparable to the Greek -kratia (as in dēmo-kratia) in that it is a bit more natural of a force. At least that's how “iktidar” feels in Turkish. Its derivative “muktedir” is a person in control, someone of high competence and social standing. It’s also a very masculine term. “İktidarsız,” literally meaning “someone without iktidar,” is the clinically used word for male impotence.

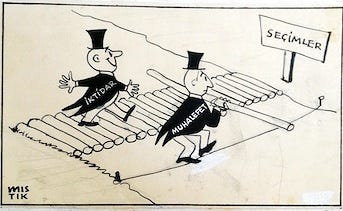

In the political context, iktidar suggests a broader command of a country, yet usually one that remains within the constitutional structure. So people will speak of an “AK Parti iktidarı,” “Erdoğan iktidarı,” and the opposition can speak of a future “when we’ll be iktidar.”

Take for example, Erdoğan's statement “we have become a political iktidar, but we haven't become an iktidar in the social and cultural spheres.” He is saying that he and his movement have established a dominant position in the sphere of politics, but that they haven't been able to do the same in the sphere of culture (the government’s lack of cultural iktidar comes up often in Turkish politics, and is possibly the subject of a future post).

In Turkey's recent political history, those two terms have largely been enough to describe things. More recently though, we have seen an increasing use of “rejim,” the Turkish cognate of the French régime.

As in other languages, the term can be used in a neutral way to describe a form of rule (from the latin regimen meaning rule), such as a “democratic regime” or a “farm subsidies regime.” Some of the recent use has been in this direction. Since the constitutional change in 2017, Turkey’s form of government has effectively changed, and people therefore speak of a “presidency regime.”

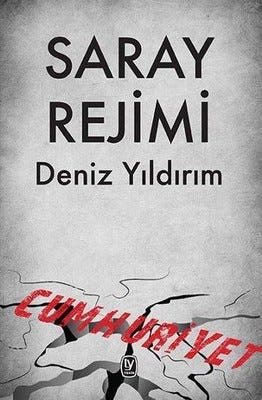

That’s where things start to get blurry, because these days, the term often tips over into its explicitly negative meaning, almost the way one might speak of the Assad regime, or Iran's regime. I say almost, because most people still feel the need to soften it with modifiers. The most common one might be “Saray rejimi” (the palace regime, referring to the newly built presidential complex) which, CHP politicians like chairman Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, spokesperson Faik Öztrak and deputy leader Selin Sayek Böke all use regularly. Sometimes they’ll say “ucube saray rejimi” which translates to something like the “freakish palace regime,” highlighting the unique nature of Turkey’s current structure of government.

There's other forms, like “AKP rejimi” or “tek adam rejimi” (one-man regime) people use, and they all emphasize slightly different aspects of the powers that be. Demirtaş, for example, refers to the “Erdoğan rejimi,” to highlight the personalized nature of the president’s rule. I’d say that people tend to use “AKP rejimi” when they talk about the systemic fusion between neoliberal rationale and authoritarian rule, something especially visible in the construction sector. There, the point is precisely that the problem isn’t just personal, but a product of a global force. These terms don’t necessarily contradict each other, it’s mostly a matter of emphasis.

Calling the incumbent structure a regime, of course, implies that it is illegitimate. “But there’s elections!” I hear you saying, “and if the elections weren’t competitive, as they aren’t in a place like today’s Russia, people wouldn’t talk about them as much as they do. This talk of “regime” is nothing but opposition hyperbole! These people know they can’t win elections, so they’re trying to undermine the man who can!”

Easy there, Mr. Strawman, you’ll bust your stitches. I’m afraid it’s perfectly possible for popularly elected people to systematically violate a country’s constitution, and therefore be considered illegitimate. It has been happening in Turkey, as well as in a lot of other countries, today and across modern history. There is vast documentation and analysis on such cases (my own drop in that bucket is here). Essentially, it means that the elected government systematically breaks the rules to enrich itself and crush its legitimate opponents. In Turkey’s case, the last institution left standing is the national election. It is the only institution that the government still fears.

The government’s systematic violation of the constitutional order occasionally becomes more visible, as in the controversy over Erdoğan’s repeated candidacy for reelection. The opposition has argued - plausibly, as far as I understand - that Erdoğan has served two terms already, and that according to the constitution, he can only run again in the case of early elections. Erdoğan disputes the claim, saying that 2017 marked a reset in his term limits, and that was implied and didn’t have to be stipulated in law. When voices in the opposition called on Kılıçdaroğlu to campaign on this, he said “let’s say we spoke out about this [to them Supreme Electoral Council, YSK]. Who appoints YSK members? Erdoğan. There is nowhere to raise objections.” The only way out, he later said, would be to secure the conduct of the election on that day. “If we trusted the YSK we wouldn’t specifically work for ballot box security,” he said, “we don’t trust the judiciary, the YSK, it’s that simple.”

Hence “rejim.” I’d say that people who use “rejim” still use “iktidar,” sometimes switching back and forth to describe slightly different things. HDP co-chairman Mithat Sancar for example, said in an interview last year “this regime is a regime that is the enemy of freedoms. This iktidar is most afraid of the free press.” He doesn’t use those words interchangeably, he uses them together to be comprehensive. So he will say that his party will stop “this regime and this iktidar,” meaning that they will stop the government and the pattern of right-wing (some would say fascist or post-fascist) politics it represents. Most people who use those terms will seldom speak of a “hükümet” any more. It’s too polite a word to describe the cobra that’s crushing the life out of you.

The one major opposition part that doesn’t use rejim is İYİ. I’ve been looking through their statements, and it’s conspicuously absent. Akşener has said things like "[Erdoğan,] you held a constitutional referendum in 2017, you changed the regime" which is descriptive, but she hasn’t used the term in the pejorative sense. Instead, she has been ringing out the cry “yaşasın özgürlük, kahrolsun istibdad” meaning roughly “long live freedom, down with tyranny.” This was the slogan of the Young Turk revolution against Sultan Abdulhamid II, leading to the Empire's Second Constitutional Era in 1908. The slogan was a Turkish version of the French Revolution's “liberté, égalité, fraternité.”

The word “istibdad,” stems from the Arabic root بَدَّ (badda) meaning apart. It describes the personalized rule of one man and the curtailment of constitutional freedoms. I think Kemalist Turkey got rid of the term in favor of “tek adam,” which means “sole man” in more contemporary Turkish. Tek adam, however, can be either positive or negative. Şevket Süreyya Aydemir's Atatürk biography bears that title because it approves of the man in question. Since those days, however, the “tek adam dönemi” of Atatürk and İsmet İnönü has acquired a negative connotation.

Calling Erdoğan a “tek adam” therefore has its complications. It could imply that he's a dictator, but it would also invite comparison to Atatürk, which you probably want to avoid if you’re in the business of criticizing Erdoğan. Calling him a dictator (simply “diktatör”) outright would probably invite an expensive lawsuit. “İstibdad” short-circuits all that and draws a line from Abdulhamid II to Erdoğan, which everyone, including the Erdoğanists, can agree exists. “Tek adam” and “tek parti dönemi” (the single party era, 1923-1950) are therefore used by Erdoğanists against the CHP. In this way, everyone has their very own pejorative terms for everyone else.

It’s smart of Akşener. Rejim would be what right-wingers call “leftist jargon.” With istibdad, she lays heavy criticism against Erdoğan without and makes it sound (despite its history) wholesome and authentically national. Most importantly, she avoids calling into question the legitimacy of the commander-in chief.

Announcement:

I’m going to do a weekly email for paid subscribers in which I’ll briefly summarize the things I’ve been reading and watching that week.

Keep in mind that I’m writing a book on Turkish politics while doing a PhD on Nietzsche, so it’s going to be a mixed bag of things. I also consume an inordinate amount of lowbrow literature and video, so caveat lector!

If you haven’t already, you can get those emails by upgrading your subscription below. This is how I pay the bills, so please consider supporting Kültürkampf if you can!