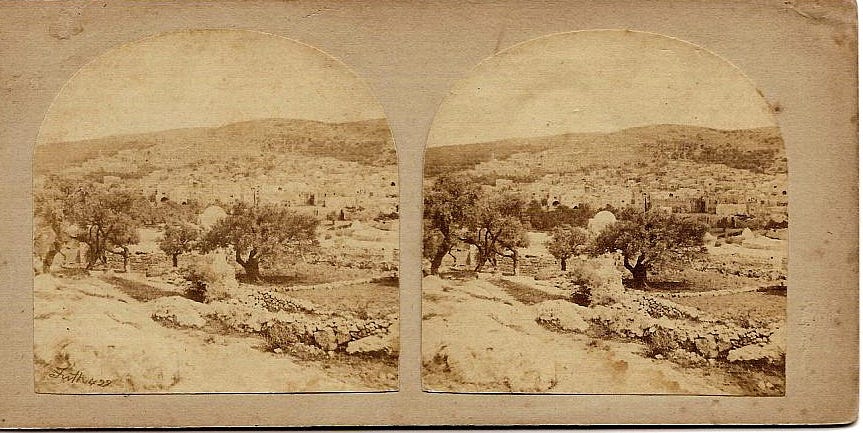

In the summer of 2013, I spent a couple of months at Birzeit University in the West Bank. I was supposed to be studying Arabic, but spent most of my time hopping around the place. It was nice. I made friends with university students, toured villages and olive groves, and had dinner with Turkish diplomats in East Jerusalem.

Palestinians would first think that I was European, and when I told them where I was really from, they’d explode into a flurry of pleasantries and questions. The Turkish TV show Aşk-ı Memnu (“Forbidden Love”) was wildly popular at the time, so that came up pretty quickly. People kept saying I looked like “Mohannad,” who, as I came to learn, was the Arabic name for Kıvanç Tatlıtuğ’s character, the show’s main heartthrob. I knew that this was extremely generous, but I still enjoyed it. I felt a sliver of what Americans must feel when they’re touring some Italian village and someone in broken English wants to talk to them about Ross and Rachel from Friends.

This being Palestine of course, there was more to talk about than pretty people on TV. I was a graduate student at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) at the time, and had studied the conflict before going. It was as described. The checkpoints, the watch towers, the power outages, the nightmarish logistics, all made life impossibly difficult for people. This was a country that was slowly being etched out of existence.

I did the infamous walking tour of Hebron, where Israel has set up a settlement in the heart of a bustling Palestinian city. The settlers and soldiers there are very aggressive, even towards tourists. Our group met in central Hebron and went into the closed off Israeli settlement for a few hours. The tour guide was Palestinian, and most of our group came from Europe and North America.

I took notes during the tour and typed out a detailed description once back in my room. I thought I might publish it somewhere, but never got around to it. Instead, I sent it to a few friends and family members back in Ankara. I’ve been thinking about those days since the October 7, so I went back to read my dispatch from a decade ago.

My take on the occupation wasn’t unique. It’s an incredibly well documented conflict, so that shouldn’t be surprising. What’s more interesting to me is my 25-year-old self. What was important to me and why? I think there’s something to be learned here that maps on to our political moment.

I’ve translated some of the paragraphs and edited them lightly for clarity:

As we tried to enter the shops, soldiers stopped us. They said only foreigners could enter, and Muslims had to stay on the other side. An American Muslim among us got angry, took out his passport and told the soldiers, “I am a Muslim and American Citizen! Are you going to stop me? Am I not allowed to go in too?” But the soldiers wouldn’t be provoked and just let him in. What they really wanted was to keep our Palestinian guides from entering. They didn’t see the leftist American Muslim as a threat.

I was upset and didn't feel like going into the shops. I saw our guides sitting on the short walls along the street, and joined them. I met someone who worked at Hebron University. I’ve gotten used to the sparkle in people’s eyes when they find out I'm Turkish. They always say “Wallahi? Ahlan wa sahlan!” This guy’s name was Tarık [Tariq], and said it too. Then he proudly proclaimed that he was also of Turkish origin. He told me that there were four big Turkish families in Hebron. He wrote their names on a piece of paper for me and said I could get more information about them at the Al-Aqsa Library.

Meanwhile, the Israeli soldiers were getting restless and asked us to get up from the wall and move to the other side of the street. At first I ignored them, but they continued to warn me, so I got up without looking at them, and walked to the other side while continuing the conversation with Tarık. It was the first week of Ramadan, and being under the sun had made us feel tired anyways.

Most of the civilians accompanying the soldiers were young and spoke English with American accents. With them was someone who looked like a settler, dressed in black and white. They were walking down the street, and just as they passed us by, one of them started singing something in Hebrew, and the others eagerly joined him. Then one of them ran back and insisted on pushing another bag of chips into the hands of a hefty-looking soldier. When Tarık saw that I was watching the situation, he said, “they want to show us that they treat their soldiers well.”

The group was now moving away, and one of the British tourists from our group took out his camera and wanted to take pictures. One of the Israelis turned around — a boy wearing a basketball jersey, black fedora and dangling side curls. He grinned and struck a pose, making a 'V' sign with his fingers in the style of an American rapper, then turned back and continued on his way with his friends.

I titled my notes “Defeated Civilization.”

Reading it now, what strikes me is that there was a difference between those of us who were from Muslim backgrounds and those who weren’t. That American Muslim, for example, almost wants the soldier to refuse him entry. He wants to share in a little piece of the Palestinian victimhood. The soldier is experienced enough to refuse him that.

I’m being just a little more clever by skipping the moral jujitsu and just staying outside. The American Muslim and I seem think that there’s a difference between us and the non-Muslims on the tour, and I clearly feel in the writeup that that’s important to maintain. To me, or more accurately, to the politics I’m channeling here, this isn’t a humanitarian crisis, or racism, nor even a nation on its knees. It’s a civilizational crisis. That means that it’s not just about the Palestinians, but “our” collective defeat as the Muslim world.

That’s probably why I felt eager to connect to Palestinians on that level, and if I may be so presumptuous, why they often seemed eager to connect with me. I think this was made all the more exciting by the presence of a language barrier. It felt like we were excavating something that had been lost for generations, and that this would somehow be the way out of the current state of affairs. Note that that’s a right-wing position. You’re in search of tradition, civilization, a subjective basis for your social hierarchy.

That’s not what most Westerners feel when they go on the Hebron tour. They tend to frame what they see in terms of an egregious human rights crisis, a great sin. They’re aware that their countries enable Israeli settlements, feel complicit in it, and take steps to campaign against it. That’s a left-wing position. They’re turning their criticism against their own countries, media environments, and deeply ingrained state policies. For them, it’s settler colonialism against international law.

Those, of course, aren’t the only two responses there are to the conflict. You can be a leftist Muslim in France and develop a highly sophisticated systemic analysis. Many Islamists will also make use of leftist insights into the Western condition. Still, I think the two categories above are the most prevalent. In effect, this means that two groups want want some of the same things (ending the occupation), for different reasons.

Since October 7, the Western left and the Muslim right have aligned in disharmony once again. The right in Israel and the United States have ridiculed this, which attests to a degree of validity. It’s true of course, that the progressive protestors across Western campuses and the people burning Israeli flags in Istanbul and Cairo wouldn’t be able to live together. I don’t think that’s a problem by itself, but it does point to a larger problem.

Let’s for a moment get back to my own story, because I’m not sure I’d write home in quite the same way.

I went back to Ankara after graduate school and continued my job as a think-tanker. Turkish politics in the mid-2010s was turbulent, to say the least. In its early years, the AK Party government had risen to power by allying itself with the liberals, but now it was drifting back to the far-right. We went through some kind of vote or referendum pretty much every year, saw purges, a coup attempt, several wars on our borders, and a refugee crisis that’s still unfolding. Above all, we saw how a right-wing government consolidated into an immensely centralized regime. Like many children of middle-class conservative families, I became disillusioned with nationalism, and certainly abandoned any sense of civilizational exceptionalism.

When something like the Gaza War happens, I still find that I agree with Erdoğan more than I otherwise would. The international sphere is where he can still be the underdog. But he also can’t help but use the conflict as grist to his mill. His legitimacy, after all, is based on the civilizational clash, so he pulls it closer at every opportunity. Here’s Erdoğan at the Great Palestine Rally:

You shed tears for those who died in Ukraine, but why are you silent for those who died in Gaza? O [Western countries], I am calling out to you! Do you once again want a struggle between the crescent and the cross? If you are in such an effort, know that this nation is not dead! This nation is standing tall! Know that again and again, with the same form and determination, whatever we are in Libya, whatever we are in Karabakh, that is what we are in the Middle East.

It reminds me a bit of the American Muslim talking to the Israeli soldier above. And if you think that’s just rhetoric to garner votes, you haven’t been paying attention.

The civilizational posturing among Islamists has probably led to far too great an emphasis on the armed struggle, and too little on organized non-violent activity, like massive strikes and demonstrations. Ending Apartheid requires more political imagination. People like Gandhi, Mandela, and King knew that. The Palestinian left knows it too.

“When something like the Gaza War happens, I still find that I agree with Erdoğan more than I otherwise would. “

Why feel embarrassed? Maybe you like justice and human dignity.

When your başkan supports that you agree with him.

When he acts contrary to those values you don’t.

Really good piece. I wonder how much of Turkey's politics is driven by the reaction you describe and its opposite. If Turks in Muslim countries routinely get sparkling eyes and a grin when they reveal their origin, and Turks in Western countries get a much less pleasant reaction due to stigma, is it any surprise that anti-Western sentiment is going to be an important factor in politics?