Can Turkey be a melting pot?

Erdoğan's migration policy entails a radical vision for the country

At his UN General Assembly speech, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said:

The main opposition in our country has threatened to expel all refugees if they come to power. We are just the opposite. We are going to continue hosting refugees, just as we have been.

He’s right. The opposition wanted to stop immigration. Erdoğan opened up Turkey for immigration at all levels.

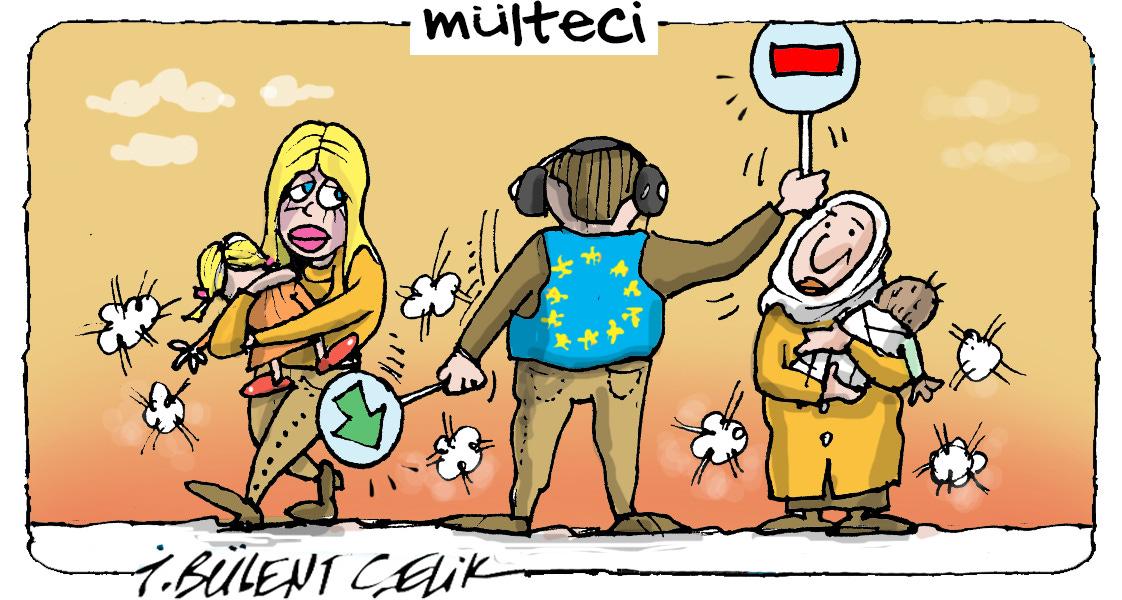

From a Western perspective, “authoritarian” and “xenophobic” go hand in hand. Stopping incoming migrants is the core of the agenda for European right-wingers like Giorgia Meloni and Viktor Orbán. In the United States, Donald Trump built his reputation with the “Muslim ban” and the wall on the Mexican border. So Erdoğan really bucks the trend here. He’s clearly on the reactionary right along with these figures, but he’s also enthusiastically pro-migration, more so than the most liberal regimes in the West. What does that mean? Is Erdoğan a humanitarian after all? Is he a closet liberal?

Not quite. I think there is a rationale here, and it is predicated on liberal economics and biopolitical engineering.

As far as I can see, there are three groups of people coming to Turkey. The first, and by far largest, are the least fortunate: refugees from war-struck Syria and Afghanistan, as well as economic migrants from the Central Asian republics, the Caucasus, and sub-Saharan Africa. These people often work in the informal sector and earn below the minimum wage. The second category are affluent people from non-Western countries, mostly the Gulf. They like to visit the cooler, lusher parts of the country, like Sapanca and the Black Sea coastline. Unlike Western tourists, many buy property, get citizenship and are sympathetic to the Islamist government. A third, and much smaller group, are middle-class Muslims in Western countries who want to live in a Muslim-majority country. (I touched on this here.) While some migrants from the Caucasus and Africa are from different faiths, the vast majority are Muslim.

Note that Turkey’s transformation into a major destination for migrants happened very, very recently. It started with the Syrian civil war in 2011, when the people who came in were called “guests,” (and they often still are,) not entirely unlike the Gastarbeiter in post-war Germany. Then, in the mid-2010s, the government began to experiment with new economic models and found that groups one and two above were helping to keep the country afloat. So they made it easier for them to come in. To be blunt, poor migrants drove down labor costs (and brought in EU money). That’s what former interior minister Süleyman Soylu meant when he said that “factory owners would be the first to revolt” if Syrians left. Rich migrants, meanwhile, injected money into tourism and retail, boosting demand. Group three is starting to bring in skills and know-how, which Turkey dearly needs as its most skilled workers are leaving for Western countries.

From the perspective of the bosses, that’s all great.

What about the political dimension? After all, it’s voters whose wages are driven down and who are being priced out of their homes. And beyond electoral concerns, Turkish nationalism isn’t exactly pluralistic (ask the Kurds.) Just as in Europe, right-wing voters want to live “chez nous,” they want the consistency and simplicity of one nation, one language. Constant social change, especially in times of economic hardship, is upsetting to them. That isn’t just the case for opposition voters but for Erdoğan’s supporters as well.

So what is the presidency’s position on this? One could argue that they are trying to get the economic benefits while trying to control the political fallout, but I don’t think so. I don’t think Erdoğan is really focused on economic gain. He (if not those around him) understands that wealth accumulation has to be tied to a political project. I think he considers Turkey’s political and demographic transformation as a net benefit as well. That’s what makes this interesting. The Erdoğan palace is going for a radical revision of Turkish citizenship and national identity. This is part of its broader political strategy to cement its regime further.

This is a very delicate policy to roll out. They are aware that most of their voters stayed with them despite their immigration policy, not because of it. So on the one hand, they say that things are going to remain the same. Government spokespeople and journalists still refer to Syrians as “guests” and talk tough on border security. They make promises of sending people back while maintaining conditions for people coming in.

One the other hand, the governing class increasingly see that they have to adjust people’s conception of their country’s demographic makeup. I suspect there’s going to feel their way there through specific events. A couple of weeks ago, for example, a man in Trabzon assaulted a tourist from Kuwait. He apparently thought that the Kuwaiti man, dressed in his traditional garb, was being disrespectful to a police officer. (He wasn’t.) This was covered widely in Arab media.

Gerçek Hayat, an Islamist magazine, put out this video where pro-government journalists got together to denounce racism against Muslims in Turkey. They aren’t explicit about this, but they claimed to speak on behalf of what they consider to be a conservative majority and against a racist, Kemalist, secular minority. The video is entitled “we are one nation,” and that nation isn’t the Turkish nation, it’s the nation of Muslims.

It reminded me of an exchange I had with a pan-Turkic nationalist friend some time ago. I was teasing him about how narrow the difference between the Islamists in government and the pan-Turkic (Ülkücü) movement was. “They’re just as nationalist as you guys” I said, and my friend turned around and quipped “yeah, but of which nation?”

Gerçek Hayat is founded by Hakan Albayrak, a very prominent Islamist journalist, and the people in the video aren’t exactly people who go out on a limb on these issues. These things are most likely coordinated at the presidential palace. They want to soften up Turkish nationhood and make it more civilizational, and particularly pan-Islamic. Within that civilization, Turkishness would still be a privileged cultural identity, but its exceptionalism would come from being the first among many equals, the core culture of an imperial force.

Does this make Erdoğan different from the European and American reactionary right? Yes, but not in the way you think. This kind of openness to migration might trespass on ethnic nationalism, but it is still civilizationalist.

In that sense, far-right leaders in Europe aren’t really against immigrants either, they’re against immigrants from other “civilizations.” That’s why taking in the Syrians after 2011 was considered a big burden. Angela Merkel’s “wir schaffen das” moment in 2015 cost her dearly. Ukrainian migration after Russia’s invasion in 2021, though, wasn’t nearly as big a political issue. Europeans felt proud to roll out the mat.

The common denominator of revanchist nationalism isn’t that it’s against immigration, it’s the idea that one’s core collective identity has been polluted and needs to be restored. That why the “re-” suffix is so appropriate (reactionary, revanchist, restorationist, or in Trump’s case, making America great again). In the West, that’s a political minority that campaigns on the fear of biological replacement (be it by Jews in the past, or Muslims today). The revanchist right thinks about things like fertility rates and restoring their ethnic stock, while liberals find such discussions inappropriate to begin with.

In Turkey, the power dynamic and narrative is different. The revanchist right is no longer a fringe group, it has been in government for more than two decades and has redesigned the state. Unlike its counterparts in Europe, however, it believes that the minority that pollutes the core identity of its nation isn’t coming in from abroad, but has been in the country all along: it’s the leftists, liberals and Kemalists, the civilizational traitors.

How to deal with these people? Well, Turkey’s Islamists never had trouble talking about the details of the nation’s biological existence. This is a movement that used to talk about contraception as a Jewish plot to curb Turkey’s population. At every single wedding he attends, Erdoğan publicly urges the bride and groom to produce at least three children. During a visit to Baku, he recently expressed his pleasure at Azerbaijan’s growing population, saying “when we say population, that is the power of a country. That changes paradigms.” To leaders like this, politics isn’t just about winning elections and scoring international agreements, it’s about out-existing the enemy.

What can be said for Turkey’s Islamists is that they aren’t scientific racists, and despite their rhetoric, they aren’t even all that picky about religious belief and observance. What they care about is allegiance to the leader, the new regime he has created, and the idea of geopolitical rise entailed therein. That makes them more dynamic and open to population flows.

Still, I’m not sure Erdoğan’s attempt to revise Turkish political identity will succeed. Even the Kemalists had limited success doing that at the beginning of the Republic when people like Ziya Gökalp tried their hand at fashioning a European-style ethnicity-based Turkishness. The opposition carries that tattered banner today, and it’s probably why they can still count on half the population’s support.

The Erdoğan regime’s experiment is more radical, and breathtaking in scope. There’s much more to say about it, but I’ll leave it here for now.

Whatever you think of Erdogan and his political objectives, if the end result is a more multicultural and cosmopolitan Turkey, how is that a bad outcome for even secular liberals? The alternative vision is more exclusionary and illiberal (and geo-politically naive).