This is the second volume in the series where I unpack phrases in Turkish political life. (For Vol 1).

I got the idea from Tanıl Bora’s Birikim column on political phrases, some of which were compiled into a book. Bora is an extremely prolific scholar of political ideas and is best known for his work on Turkish nationalism.

İrfan Aktan did a two-part interview with him this week, and it made quite a splash.

We are probably approaching a time in politics where the nature of Turkish nationalism is going to be discussed in a way it hasn’t been for some time. Below, I’ve covered two phrases that might help you think about these issues.

Being of Turkey [Türkiyelilik]: this is a deeply imperfect translation, but bear with me - it’s one of those terms that marks the intersections between Erdoğan and the progressive movement.

I’m not sure who first came up with the word Türkiyeli (there are historians tracing it as far back as the 1920s), but it was Erdoğan who injected it into mainstream use in recent years. In his victory speech after the 2014 election, then-PM Erdoğan said:

“Before the Muslim, the Jew, the Assyrian, the Yazidi, there is the Türkiyeli. Before the Alevi and Sunni, there is the Türkiyeli. Before the Turk, the Kurd, the Arab, the Laz, the Georgian, the Bosnian, the Circassian, the Greek [Rum], the Armenian, there is the Türkiyeli.”

What did he mean?

Turkey’s model of nationalism is close to the continental European form, rather than, say, the Anglo-American one. This means that in its classical conception, everyone in Turkey is supposed to be a “Türk” in the way that citizens of Germany are supposed to be a German. Yes, there might be German citizens of Polish or French origin in Germany, but the idea, especially after a couple centuries of devastating wars, was that they were sort of homogenized into a common German identity. The terms “British” or “American” aren’t necessarily bound up with ethnic and linguistic identities in the same way.

In recent decades, we have developed a greater sensitivity to how these ethno-linguistic national myth doesn’t line up with reality. There is, most notably, a large Kurdish population in Turkey that doesn’t believe that the word “Türk” describes them. This means we need a word for a group of people who are not Turkish but are of Turkey. The suffix “-iyeli/-lı” in Turkish denotes a regional belonging. So a “Suriyeli” is a Syrian, and a “Ankaralı” is a person from Ankara. Türkiyeli is someone of, and/or from Turkey.

It did not exist before because everyone from the country was presumed to be a “Türk”. The idea behind Türkiyelilik is therefore that the presumption of national homogeneity in Turkey needs to be broken down. The country is to be a bit more like the United Kingdom, a union of different national groups.

You can get to Türkiyeli from at least two different points of view.

The Islamists believed - since long before the AK Party government - that the Kurdish question could be solved by disaggregating the Kemalist project of a European nation-state and assuming a pan-Islamic imperial model. When Erdoğan was holding his 2014 victory speech, he was pursuing the peace process with the PKK, probably with that model in mind.

Progressive and leftists, believed that the Turkish nation-state was inherently oppressive and sought to make it more inclusive. They approached Türkiyeli as a word that could take the edge off of the nation-state. Leftist language continues to reflect that idea. HDP politicians don’t usually use the word “millet”, meaning “nation”, they speak of “halklar,” meaning “peoples.” Think of the name “Halkların Demokratik Partisi” (“the People’s Republican Party”) as “Türkiye Demokratik Partisi,” with the “Türkiye” switched out.

The Erdoğan government buried its post-national aspirations with the peace process in 2015, and does not use Türkiyelilik any more. It still has a fairly expansive definition of the nation, however, which is partly why it has chosen a fairly lenient immigration policy. The progressives, meanwhile, have taken Türkiyelilik as their own.

I think the discussion around Türkiyelilik is going to be more important as the Erdoğan government loses power. The nationalists most likely to replace the Erdoğan believe in a much more classical nation-state. Anti-immigration sentiment is moving front and center of public discourse in a way that makes both the Erdoğan government and progressives uncomfortable (for different reasons and to different degrees). Ümit Özdağ, the leader of the anti-immigrant Victory Party, likes to draw attention to this parallel between Islamists and progressives for that very reason.

I noticed the other day Mehmet Akif Okur, one of the foremost Ülkücü intellectuals, tweet this thread on the subject (you can click on it to translate).

Türkiyelilik, he argues creates tension that “agitates the narrowing and hardening of the psychology of wider Turkishness around a new core.” Turkishness (Türklük) he suggests, is already inclusive.

Expect to see more of that.

The Kurd shall not see his mother [Kürt Anasını görmesin]: this is the last line from a joke.

There’s two prisoners on death row, one Kurdish, the other Turkish. These guys are sworn enemies and have been fighting constantly.

It’s the night before they are to be hanged, so the warden visits them to ask each for his dying wish.

“I love my mother very much,” says the Kurd, “I wish to see her one last time before I die.”

This is no surprise. The warden knows that both mothers are outside the prison gates, crying their gut out.

The warden now turns to the Turk. “Do you also wish to see your mother?” he asks.

“No” says the Turk.

The warden is startled. “Then what is your wish?”

“I wish for the Kurd not to see his mother” says the Turk.

The last line has become shorthand among leftists and/or Kurdish nationalists to describe the force they have faced all their lives. It’s an old phrase, but it has most recently been used with regard to Turkish policy in its eastern provinces in 2015 and Syria.

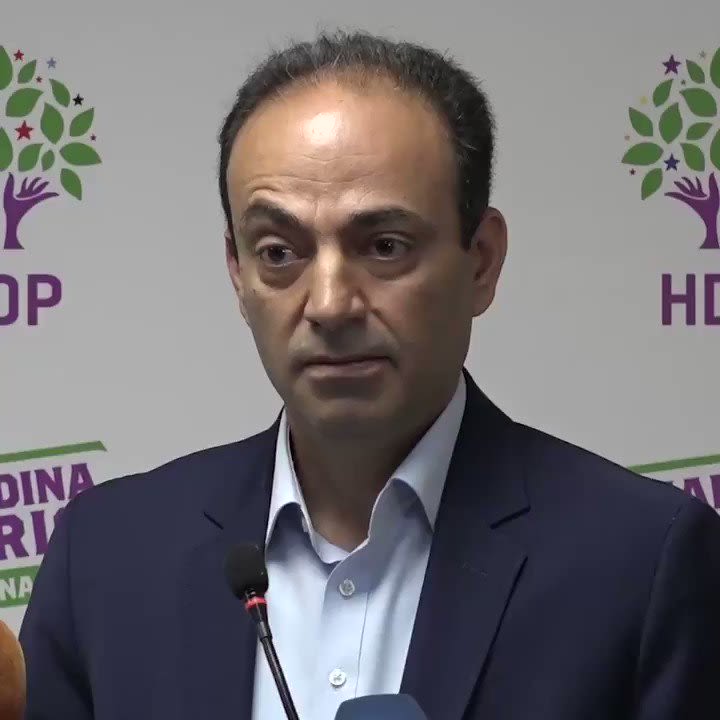

Here is former HDP MP Osman Baydemir using the phrase in 2017. “When the issue is the Kurd, it is ‘the Kurd shall not see his mother. When the issue is the Kurd, it’s ‘the Kurd’s will shall not come out in the open’”, he says. He speaks of a gathering at the UN: “Foreign minister of Tehran, Baghdad and Ankara talk about ‘how will the Kurd not see his mother.’ For god’s sake, what have these people done to you?”

It’s Ankara’s policy not only to break up Kurdish political formations in Turkey, but also beyond its borders as well. People sometimes joke that if Turkey knew that the Kurds were forming a state in Australia, they’d mobilize the navy. Something in the Turkish psyche, the idea goes, simply subsists on enmity to the Kurds and Kurdishness. Turkish nationalists would respond by saying that the PKK is a demonstrably real threat to the Turkish nation-state.

I think much of it comes down to (to mix my terms here) whether you believe in Türklük or Türkiyelilik. Is Türkiyelilik a slippery slope that will lead to the irreversible loss of the only reservoir of meaning left in the world (the nation)? Or is it a revision that can make nationhood a little more realistic, and thus save it from total irrelevance? How are the millions of new arrivals in Turkey going to change this discussion?

When the Erdoğan government eventually ends, these are some of the questions it will leave behind.