There’s a lot to be said about the events transpiring in and around Syria, but the political analysis will have to wait. Assad has fallen, and it is time for celebration.

Readers of Kültürkampf will already know my friend , and it’s my distinct pleasure to host his essay on this occasion.

All the best,

Selim

I have been following a ritual in Ankara, where I lived for several years, and now in Istanbul. I wake up, make coffee, and spend around 45 minutes on X. Then, I shave, clean my place, and shower—it is my Sunday ritual. This Sunday was going to be a little different. It marked the 9th year of my father’s passing. That’s usually a day when our family – spread out as we are – commemorates my father. We look at his old photos; we call each other to tell stories. We remember him.

This Sunday, December 8th, however, I woke up to a text from my mother. “Good morning, and congratulations to us all,” the text read. I immediately went to my X account, which was full of videos from Syria about the fall of the regime. I was shocked. It felt unreal.

I was born and raised in Damascus. Hafez Assad died when I was twelve. I remember how scared people were to talk about it. To say that you could hear a pin drop would not exaggerate the silence in the streets. One day soon afterward, we were at a relative’s home. I was fascinated with the song “Hasta Siempre, Comandante,” commemorating Che Guevara of all people, and I listened nonstop. I can’t remember whether it was popular at the time or if it was just me. While at the relatives' place, I played the music on a computer and turned up the volume. It took around four seconds for my cousin to storm into the room and yell, “turn that shit off! You want us to be sent behind the Sun?” That was a phrase people often used. You didn’t play music when the country was pretending to mourn. And if we had gotten into trouble? Could my parents have told the mukhabarat that I was just a kid? Or perhaps prevaricate a little, saying that the “Comandante” in question was Assad? It certainly would have been a lot to think about someplace “behind the sun.”

My family and I left Syria in 2012. We left because our house was shelled in a crossfire between the rebels and regime forces, injuring my father and I. It was only in 2016 that I realized a shrapnel had been in my chest since that day. It stayed with me until very recently, when I underwent minor surgery to have it removed.

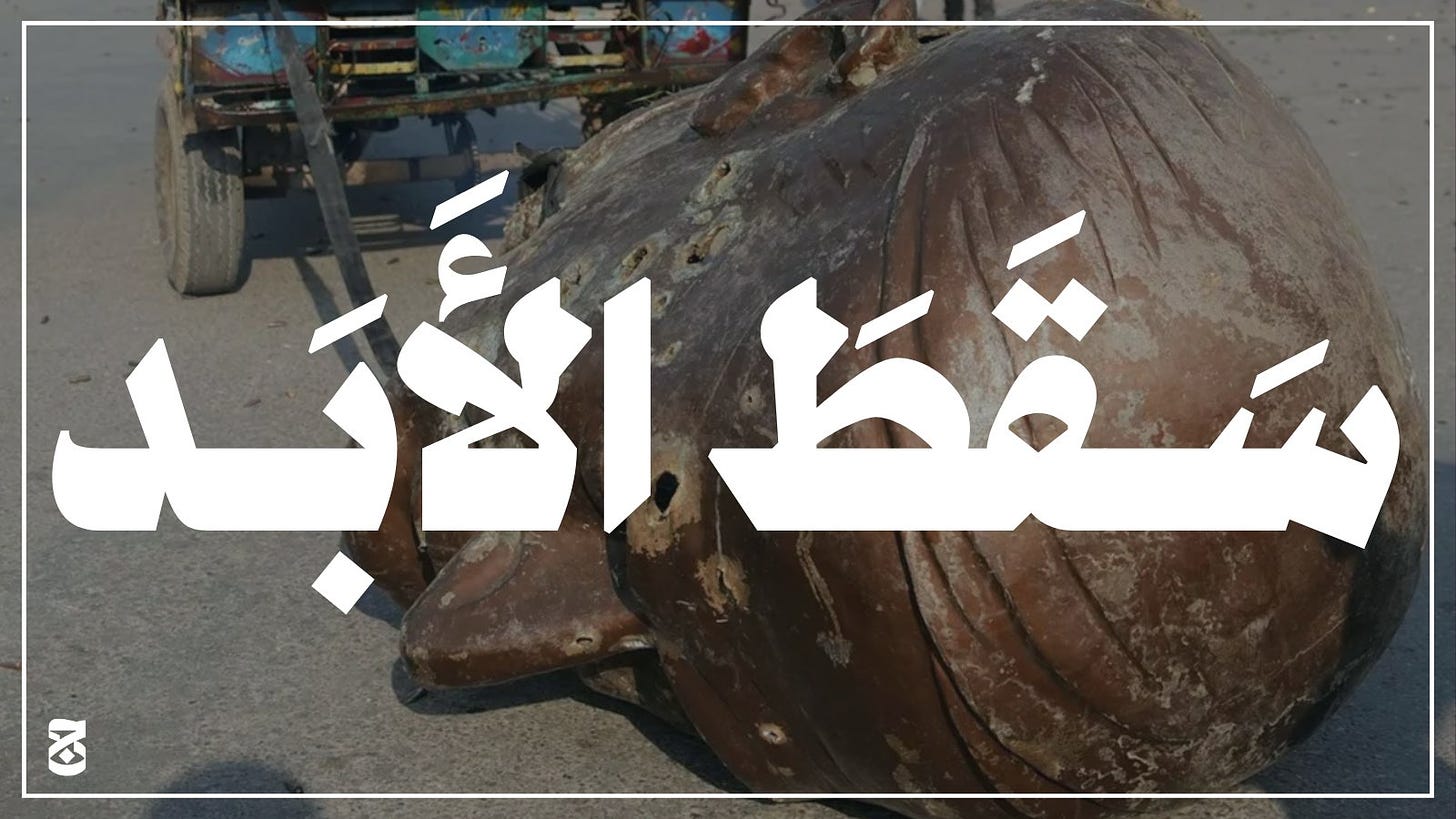

Our experiences, of course, are a drop in the ocean of what tens of thousands of Syrians suffered during the Assads’ reign of terror. One thing that was particularly awful about it was how permanent it made itself out to be. The official line was that Hafez Assad’s presence was with us “for eternity.” Well, no more. My social media feed has been buzzing with the slogan “eternity has fallen.”

When my mother called this Sunday morning, she was filled with joy. “I am very happy,” she said. She then sobbed, and I sobbed with her. She wanted to contact my sister in Austria, but the time difference was inconvenient – a problem that many Syrians probably had in those moments. A strange mix of trauma and joy swirled up in us. Two childhood friends of mine in two different countries started texting me. “It is all green,” one typed, commenting on the live map of our country. “I just want to see [Assad] humiliated in a courtroom,” typed the other. Most of the ensuing conversation was laced with creative profanity that doesn’t translate well, so the Kültürkampf reader will be spared. I think my friends were in control of their emotions. I wasn’t. I put down the phone, hugged my fiancé, and cried out of happiness and confusion. The HTS military offensive named “Deterrence of Aggression” was still unfolding, but the details were coming in too quickly. I felt overwhelmed.

I wanted to be with Syrians on the streets. Around noon, my fiancé and I decided to go to the Akşemsettin neighborhood in Fatih. The traffic on the two-way street was bumper to bumper, with mostly Syrian drivers honking uncontrollably. The green-white-black tricolor of struggle, the first official flag of Syria (as opposed to the red-white-black of the Ba’athists), was flying out of the windows, and cars blasted a variety of revolutionary songs. It was surreal. The police officers asked the drivers to turn it down, but to no avail. Nothing could control the joy of Syrians, and the police stopped trying. On the sidewalks, groups of Syrians came up from Vatan Caddesi, chanting “Ya Allah, Bismillah, Allahuekber” from an Ottoman military march – a reflection of their integration.

I usually find it hard to be in Fatih without eating Syrian food. We decided to grab a bite at a place famous for the traditional falafel wraps and fatteh dish. It was packed. “Your table should be ready in twenty minutes,” said the waiter. We stepped outside and kept on watching the crowds. Other Syrians were standing by and watching, smiling from ear to ear, phones in hands, recording anything and everything about the day. “We aren’t refugees anymore?” asked one – a spot-on policy question, but the analyst in me felt like it was still a bit too early for it. A passerby stopped at a shop selling Syrian goods, hugged the shop owner, and said, “I can’t believe it is over!” Another shop owner was distributing free candy, and kids filled their pockets. The child in me wanted some of the candy, but I felt shy. I went in and bought a box of it.

Unlike other areas in Turkey, many Syrians in Fatih are from Damascus. Being there, smelling the food, and seeing the happiness of hundreds of Syrians brought back beautiful memories. It was as if I had built an emotional dam long ago, and now that I had almost forgotten about it, the whole thing burst open. I didn’t know what to do but cry, and I hugged my Turkish fiancé and cried some more.

It was time to go home. I calmed down, and the streets did too. My few hours in Fatih on Sunday, December 8, 2024, were the closest I got to Damascus in over a decade.